Johan Cruyff

Cruyff with the Netherlands in 1974 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Hendrik Johannes Cruijff | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date of birth | 25 April 1947[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of birth | Amsterdam, Netherlands | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Date of death | 24 March 2016 (aged 68) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Place of death | Barcelona, Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.78 m (5 ft 10 in)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Position(s) | Forward, attacking midfielder | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Youth career | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1957–1964 | Ajax | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Senior career* | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Years | Team | Apps | (Gls) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1964–1973 | Ajax | 245 | (193) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1973–1978 | Barcelona | 143 | (48) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1979 | Los Angeles Aztecs | 22 | (14) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1980–1981 | Washington Diplomats | 29 | (12) | ||||||||||||||||||||

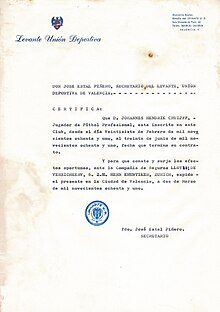

| 1981 | → Levante (loan) | 10 | (2) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1981–1983 | Ajax | 36 | (14) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 1983–1984 | Feyenoord | 33 | (11) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Total | 518 | (294) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| International career | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1966–1977 | Netherlands | 48 | (33) | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Managerial career | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1985–1988 | Ajax | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1988–1996 | Barcelona | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2009–2013 | Catalonia | ||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| *Club domestic league appearances and goals | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Netherlands professional footballer Eponyms and public art

Related |

||

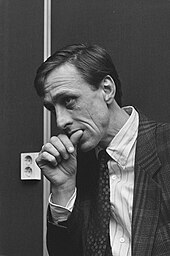

Hendrik Johannes Cruijff (25 April 1947 – 24 March 2016), commonly known as Johan Cruyff (Dutch: [ˈjoːɦɑŋ ˈkrœyf] ), was a Dutch professional football player and manager. Regarded as one of the greatest players in history and as the greatest Dutch footballer ever, he won the Ballon d'Or three times, in 1971, 1973, and 1974.[3] Cruyff was a proponent of the football philosophy known as Total Football developed by Rinus Michels, which Cruyff also employed as a manager. Because of the far-reaching impact of his playing style and his coaching ideas, he is widely regarded as one of the most influential figures in modern football, and he is also regarded as one of the greatest managers of all time.[4][5][6][7][8]

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Dutch football rose from a semi-professional and obscure level to become a powerhouse in the sport.[9][10] Cruyff led the Netherlands to the final of the 1974 FIFA World Cup with three goals and three assists; he received the Golden Ball as player of the tournament.[11][12] After finishing third in UEFA Euro 1976, Cruyff refused to play in the 1978 FIFA World Cup after a kidnapping attempt targeting him and his family in their Barcelona home dissuaded him from football.[13]

At club level, Cruyff started his career at Ajax, where he won eight Eredivisie titles, three European Cups, and one Intercontinental Cup, where he had a goal and two assists.[14][15] In 329 matches for Ajax, he scored 257 goals and provided more than 170 assists. In 1973, Cruyff moved to Barcelona for a world record transfer fee, helping the team win La Liga in his first season and winning the Ballon d'Or. In 180 official matches for Barcelona, he scored 60 goals and provided 83 assists.[16] After retiring from playing in 1984, Cruyff became highly successful as manager of Ajax and later Barcelona; he remained an advisor to both clubs after his coaching tenures. His son Jordi also played football professionally for Barcelona.

In 1999, Cruyff was voted European Player of the Century in an election held by the International Federation of Football History & Statistics, and came second behind Pelé in their World Player of the Century poll.[17] He came third in a vote organised by the French magazine France Football consulting their former Ballon d'Or winners to elect their Football Player of the Century.[18] He was included in the World Team of the 20th Century in 1998, the FIFA World Cup Dream Team in 2002, and in 2004 was named in the FIFA 100 list of the world's greatest living players.[19]

Early life

I was born shortly after the war, though, and was taught not to just accept anything.

Hendrik Johannes "Johan" Cruyff was born on 25 April 1947 in the Burgerziekenhuis Hospital in Amsterdam.[21] He grew up on a street five minutes away from Ajax's stadium, his first football club. Johan was the second son of Hermanus Cornelis Cruijff (1913–1959) and Petronella Bernarda Draaijer (1917–2007), from a humble, working-class background in east Amsterdam. Cruyff, encouraged by his influential football-loving father and his close proximity in Akkerstraat Stadium, played football with his schoolmates and older brother Henny (1944–2023)[22] whenever he could, and idolised the prolific Dutch dribbler, Faas Wilkes.

In 1959, Cruyff's father died from a heart attack. His father's death had a major impact on his mentality. As Cruyff recalled, in celebration of his 50th birthday, "My father died when I was just 12 and he was 45. From that day the feeling crept stronger over me that I would die at the same age and, when I had serious heart problems when I reached 45, I thought: 'This is it.' Only medical science, which was not available to help my father, kept me alive."[23] Viewing a potential football career as a way of paying tribute to his father, the death inspired the strong-willed Cruyff, who also frequently visited the burial site at Oosterbegraafplaats.[24] His mother began working at Ajax as a cleaner, deciding that she could no longer carry on at the grocer without her husband, and in the future, this made Cruyff near-obsessed with financial security but also gave him an appreciation for player aids. His mother soon met her second husband, Henk Angel, a field hand at Ajax who proved a key influence in Cruyff's life.[25]

Club career

Gloria Ajax and the golden era of Total Football

Cruyff joined the Ajax youth system on his tenth birthday. Cruyff and his friends would frequently visit a "playground" in their neighbourhood and Ajax youth coach Jany van der Veen, who lived close by, noticed Cruyff's talent and decided to offer him a place at Ajax without a formal trial.[24] When he first joined Ajax, Cruyff preferred baseball and continued to play the sport until age fifteen when he quit at the urging of his coaches.[26]

He made his first team debut on 15 November 1964 in the Eredivisie, against GVAV, scoring the only goal for Ajax in a 3–1 defeat. That year, Ajax finished in their lowest position since the establishment of professional football, in 13th.[27] Cruyff really started to make an impression in the 1965–66 season and established himself as a regular first team player after scoring two goals against DWS in the Olympic stadium on 24 October 1965 in a 2–0 victory. In the seven games that winter, he scored eight times and in March 1966 scored the first three goals in a league game against Telstar in a 6–2 win. Four days later, in a cup game against Veendam in a 7–0 win, he scored four goals. In total that season, Cruyff scored 25 goals in 23 games, and Ajax won the league championship.[11]

In the 1966–67 season, Ajax again won the league championship, and also won the KNVB Cup, for Cruyff's first "double".[11] Cruyff ended the season as the leading goalscorer in the Eredivisie with 33. Cruyff won the league for the third successive year in the 1967–68 season. He was also named Dutch footballer of the year for the second successive time, a feat he repeated in 1969.[11] On 28 May 1969, Cruyff played in his first European Cup final against Milan, but the Italians won 4–1.

In the 1969–70 season, Cruyff won his second league and cup "double"; at the beginning of the 1970–71 season, he suffered a groin injury. He made his comeback on 30 October 1970 against PSV, and rather than wear his usual number 9, which was in use by Gerrie Mühren, he instead used number 14.[11] Ajax won 1–0. Although it was very uncommon in those days for the starters of a game not to play with numbers 1 to 11, from that moment onwards, Cruyff wore number 14, even with the Dutch national team. There was a documentary on Cruyff, Nummer 14 Johan Cruyff[28] and in the Netherlands there is a magazine by Voetbal International, Nummer 14.[29]

In a league game against AZ '67 on 29 November 1970, Cruyff scored six goals in an 8–1 victory. After winning a replayed KNVB Cup final against Sparta Rotterdam by a score of 2–1, Ajax won in Europe for the first time. On 2 June 1971, in London, Ajax won the European Cup by defeating Panathinaikos 2–0.[11] He signed a seven-year contract at Ajax. At the end of the season, he was named the Dutch and European Footballer of the Year for 1971.[11]

In 1972, Ajax won a second European Cup, beating Inter Milan 2–0 in the final, with Cruyff scoring both goals.[11] This victory prompted Dutch newspapers to announce the demise of the Italian catenaccio style of defensive football in the face of Total Football. Soccer: The Ultimate Encyclopaedia says, "Single-handed, Cruyff not only pulled Internazionale of Italy apart in the 1972 European Cup Final, but scored both goals in Ajax's 2–0 win."[30] Cruyff also scored in the 3–2 victory over ADO Den Haag in the KNVB Cup final. In the league, Cruyff was the top scorer with 25 goals as Ajax became champions. Ajax won the Intercontinental Cup, beating Argentina's Independiente 1–1 in the first game followed by 3–0, and then in January 1973, they won the European Super Cup by beating Rangers 3–1 away and 3–2 in Amsterdam. Cruyff's only own goal came on 20 August 1972 against FC Amsterdam. A week later, against Go Ahead Eagles in a 6–0 win, Cruyff scored four times for Ajax. The 1972–73 season was concluded with another league championship victory and a third successive European Cup with a 1–0 win over Juventus in the final.[30]

Barcelona and the first La Liga title in 14 years

When players like [Gareth] Bale and [Cristiano] Ronaldo are worth around €100 million, Johan [Cruyff] would go in the billions!

In mid-1973, Cruyff was sold to Barcelona for 6 million guilders (approx. US$2 million, c. 1973) in a world record transfer fee.[33] On 19 August 1973, he played his last match for Ajax where they defeated FC Amsterdam 6–1, the second match of the 1973–74 season.

Cruyff endeared himself to the Barcelona fans when he chose a Catalan name, Jordi, for his son. He helped the club win La Liga for the first time since 1960, defeating their fiercest rivals Real Madrid 5–0 at their home of the Santiago Bernabéu. Thousands of Barcelona fans who watched the match on television poured out of their homes to join in street celebrations.[34] A New York Times journalist wrote that Cruyff had done more for the spirit of the Catalan people in 90 minutes than many politicians in years of struggle.[34] Football historian Jimmy Burns stated, "with Cruyff, the team felt they couldn't lose".[34] He gave them speed, flexibility and a sense of themselves.[34] In 1974 Cruyff was crowned European Footballer of the Year.[11]

During his time at Barcelona, in a game against Atlético Madrid, Cruyff scored a goal in which he leapt into the air and kicked the ball past Miguel Reina in the Atlético goal with his right heel (the ball was at about neck height and had already travelled wide of the far post).[35] The goal was featured in the documentary En un momento dado, in which fans of Cruyff attempted to recreate that moment. The goal has been dubbed Le but impossible de Cruyff (Cruyff's impossible goal).[36] In 1978, Barcelona defeated Las Palmas 3–1, to win the Copa del Rey.[11] Cruyff played two games with Paris Saint-Germain in 1975 during the Paris tournament. He had only agreed because he was a fan of designer Daniel Hechter, who was then president of PSG.[37][38]

Brief retirement and spells in the United States

Cruyff briefly retired in 1978. But after losing most of his money in a series of poor investments, including a pig farm, that were counseled by a scam artist, Cruyff and his family moved to the United States.[39][40] As he recalled, "I had lost millions in pig-farming and that was the reason I decided to become a footballer again."[23] Cruyff insisted that his decision to resume his playing career in the United States was pivotal in his career. "It was wrong, a mistake, to quit playing at 31 with the unique talent I possessed", and adding that "Starting from zero in America, many miles away from my past, was one of the best decisions I made. There I learned how to develop my uncontrolled ambitions, to think as a coach and about sponsorship."[23]

In May 1979, Cruyff signed a lucrative deal with the Los Angeles Aztecs of the North American Soccer League (NASL).[41][11] He had previously been rumoured to be joining the New York Cosmos but the deal did not materialise; he played a few exhibition games for the Cosmos. He stayed at the Aztecs for only one season, and was voted NASL Player of the Year. After considering an offer to join Dumbarton F.C. in Scotland, In February 1980, he moved to play for the Washington Diplomats.[42] He played the whole 1980 campaign for the Diplomats, even as the team was facing dire financial trouble. In May 1981, Cruyff played as a guest player for Milan in a tournament, but was injured. As a result, he missed the beginning of the 1981 NASL season, which ultimately led to Cruyff choosing to leave the team. Cruyff also loathed playing on artificial surfaces, which were common in the NASL at the time.

Return to Spain with Levante and second spell at Washington Diplomats

In January 1981, Cruyff played three friendly matches for FC Dordrecht. Also in January 1981, manager Jock Wallace of English club Leicester City made an attempt to sign Cruyff, competing with Arsenal and an unnamed German club for his services,[43] and despite negotiations lasting three weeks, in which Cruyff expressed his desire to play for the club, a deal could not be reached. Cruyff instead chose to sign with Spanish Segunda División side Levante in February 1981.[44]

On 1 March 1981, Cruyff took the field for the first time for Levante, starting in a 1–0 win against Palencia.[43] Injuries and disagreements with the administration of the club, however, blighted his spell in the Segunda División and he only made ten appearances, scoring two goals. Having failed to secure promotion to the Primera División, a contract with Levante fell through.[45]

In June 1981, Cruyff returned to the U.S.. He played for the Washington Diplomats in 1981 NASL season.

Second spell at Ajax

After his spell in the U.S. and his short-lived stay in Spain, Cruyff returned to playing for Ajax in December 1981. Originally, he had rejoined Ajax on 30 November 1980, before his time as a player with Levante, as "technical advisor" to trainer Leo Beenhakker, Ajax being eighth in the league table at the time after 13 games played. After 34 games, however, Ajax finished the 1980–81 season in second. In December 1981, Cruyff signed a contract as "player" with Ajax until the summer of 1983.[45]

In the 1981–82 and 1982–83 seasons, Ajax, along with Cruyff, became league champions. In 1982–83, Ajax won the Dutch Cup (KNVB-Beker). In 1982, he scored a famous goal against Helmond Sport. While playing for Ajax, Cruyff scored a penalty the same way Rik Coppens had done it 25 years earlier.[46][47] He put the ball down as for a routine penalty kick, but instead of shooting at goal, Cruyff nudged the ball sideways to teammate Jesper Olsen, who in return passed it back to Cruyff to tap the ball into the empty net, as Otto Versfeld, the Helmond goalkeeper, looked on.[11]

Final season at Feyenoord and retirement

At the end of the 1982–83 season, Ajax decided not to offer Cruyff a new contract. This angered Cruyff, who responded by signing for Ajax's archrivals Feyenoord.[48] Cruyff's season at Feyenoord was a successful one in which the club won the Eredivisie for the first time in a decade, part of a league and KNVB Cup double. The team's success was due to the performances of Cruyff along with Ruud Gullit and Peter Houtman.[49]

Despite his relatively advanced age, Cruyff played all league matches that season except for one. Because of his performance on the field, he was voted as Dutch Footballer of the Year for the fifth time. At the end of the season, the veteran announced his final retirement. He ended his Eredivisie playing career on 13 May 1984 with a goal against PEC Zwolle. Cruyff played his last game in Saudi Arabia against Al-Ahli, bringing Feyenoord back into the game with a goal and an assist.[50]

International career

As a Dutch international, Cruyff played 48 matches, scoring 33 goals.[11][51] The national team never lost a match in which Cruyff scored. On 7 September 1966, he made his official debut for the Netherlands in the UEFA Euro 1968 qualifier against Hungary, scoring in the 2–2 draw. In his second match, a friendly against Czechoslovakia, Cruyff was the first Dutch international to receive a red card. The Royal Dutch Football Association (KNVB) banned him from international games, but not the Eredivisie or KNVB Cup.[52]

Accusations of Cruyff's "aloofness" were not rebuffed by his habit of wearing a shirt with only two black stripes along the sleeves, as opposed to Adidas' usual design feature of three, worn by all the other Dutch players. Cruyff also had a separate sponsorship deal with Puma.[53] From 1970 onwards, he wore the number 14 jersey for the Netherlands, setting a trend for wearing shirt numbers outside the usual starting line-up numbers of 1 to 11.[11]

Cruyff led the Netherlands to a runners-up medal in the 1974 World Cup and was named player of the tournament.[11] Thanks to his team's mastery of Total Football, they coasted all the way to the final, knocking out Argentina (4–0), East Germany (2–0) and Brazil (2–0) along the way.[11] Cruyff scored twice against Argentina in one of his team's most dominating performances, then he scored the second goal against Brazil to knock out the defending champions.[11]

The Netherlands faced hosts West Germany in the final. Cruyff kicked off and the ball was passed around the Oranje team 15 times before returning to Cruyff, who then went on a run past Berti Vogts and ended when he was fouled by Uli Hoeneß inside the box. Teammate Johan Neeskens scored from the spot kick to give the Netherlands a 1–0 lead and the Germans had not yet touched the ball.[11] During the latter half of the final, his influence was stifled by the effective marking of Vogts, while Franz Beckenbauer, Uli Hoeneß and Wolfgang Overath dominated the midfield as West Germany came back to win 2–1.[54]

After 1976

Cruyff retired from international football in October 1977, having helped the national team qualify for the upcoming World Cup.[11] Without him, the Netherlands finished runners-up in the World Cup again. Initially, there were two rumours as to his reason for missing the 1978 World Cup: either he missed it for political reasons (a military dictatorship was in power in Argentina at that time), or that his wife dissuaded him from playing.[55] In 2008, Cruyff stated to the journalist Antoni Bassas in Catalunya Ràdio that he and his family were subject to a kidnap attempt in Barcelona a year before the tournament, and that this had caused his retirement. "To play a World Cup you have to be 200% okay, there are moments when there are other values in life."[56]

Coaching career

Entry into management with Ajax

After retiring from playing, Cruyff followed in the footsteps of his mentor Rinus Michels. In June 1985, Cruyff returned to Ajax again. He coached a young Ajax side to victory in the European Cup Winners' Cup in 1987 (1–0). In the 1985–86 season, the league title was lost to Jan Reker's PSV, despite Ajax having a goal difference of +85 (120 goals for, 35 goals against). In the 1985–86 and 1986–87 seasons, Ajax won the KNVB Cup.

It was during this period as manager that Cruyff was able to implement his favoured team formation—three mobile defenders; plus one more covering space – becoming, in effect, a defensive midfielder (from Rijkaard, Blind, Silooy, Verlaat, Larsson, Spelbos), two "controlling" midfielders (from Rijkaard, Scholten, Winter, Wouters, Mühren, Witschge) with responsibilities to feed the attack-minded players, one second striker (Bosman, Scholten), two touchline-hugging wingers (from Bergkamp, van't Schip, De Wit, Witschge) and one versatile centre forward (from Van Basten, Meijer, Bosman). So successful was this system that Ajax won the Champions League in 1995 playing Cruyff's system – a tribute to Cruyff's legacy as Ajax coach.[57]

Return to Barcelona as manager and building the Dream Team

After having appeared for the club as a player, Cruyff returned to Barcelona for the 1988–89 season, this time to take up his new role as coach of the first team. Before returning to Barcelona, however, Cruyff had already built up plenty of experience as a coach/manager. In the Netherlands, he was strongly praised for the attacking flair he imposed on his sides and also for his commendable work as talent spotter. With Barça, Cruyff started work with a completely remodelled side after the previous season's scandal, known as the "Hesperia Mutiny" ("El Motí de l'Hespèria [ca]" in Catalan). His second in command was Carles Rexach, who had already been at the club for a year. Cruyff immediately had his Barça charges playing his attractive brand of football and the results did not take long in coming. But, this did not just happen with the first team, the youth teams also displayed that same attacking style, something that made it easier for reserve players to make the switch to first team football.[58][59] As Sid Lowe noted, when Cruyff took over as manager, Barcelona of the late 1980s "were a club in debt and in crisis. Results were bad, performances were worse, the atmosphere terrible and attendances down, while even the relationship between the president of the club Josep Lluís Núñez and the president of the Spanish autonomous community they represented, Jordi Pujol, had deteriorated. It did not work immediately but he [Cruyff] recovered the identity he had embodied as a player. He took risks, and rewards followed."[60]

At Barça, Cruyff brought in players such as Pep Guardiola, José Mari Bakero, Txiki Begiristain, Andoni Goikoetxea, Ronald Koeman, Michael Laudrup, Romário, Gheorghe Hagi and Hristo Stoichkov. With Cruyff, Barçan experienced a glorious era. In the space of five years (1989–1994), he led the club to four European finals (two European Cup Winners' Cup finals and two European Cup/UEFA Champions League finals). Cruyff's track record includes one European Cup, four Liga championships, one Cup Winners' Cup, one Copa del Rey and four Supercopa de España.[61]

Under Cruyff, Barça's "Dream Team" won four La Liga titles in a row (1991–1994), and beat Sampdoria in both the 1989 European Cup Winners' Cup final and the 1992 European Cup final at Wembley Stadium.[62][59] On 10 May 1989, goals from Salinas and López Rekarte led Barcelona to a 2–0 victory against Sampdoria. Over 25,000 supporters travelled to Switzerland to support the team. Cruyff's new Barça took home the club's third Cup Winners' Cup. The European Cup dream became a reality on 20 May 1992 at Wembley in London, when Barça beat Sampdoria. Cruyff's last instruction to his players before they stepped onto the pitch was "Salid y disfrutad" (Spanish for "Go out and enjoy it" or "Go out there and enjoy yourselves").[63][64] The match went to extra time after a scoreless draw. In the 111th minute, Ronald Koeman's brilliant free kick clinched Barça's first European Cup victory. Twenty-five thousand supporters accompanied the team to Wembley, while one million turned out on the streets of Barcelona to welcome the European champions home.[63] Victories under Cruyff include a 5–0 La Liga win over Real Madrid in El Clásico at the Camp Nou, as well as a 4–0 win against Manchester United in the Champions League.[65][66][67] Barcelona won a Copa del Rey in 1990, the European Super Cup in 1992 and three Supercopa de España, as well as finishing runner-up to Manchester United and Milan in two European finals.[62]

With 11 trophies, Cruyff was Barcelona's most successful manager, but has since been surpassed by his former player Pep Guardiola, who achieved 15. Cruyff was also the club's longest-serving manager. In his final two seasons, however, he failed to win any trophies, falling out with chairman Josep Lluís Núñez, who ultimately sacked him as Barcelona coach.[68]

While still at Barcelona, Cruyff was in negotiations with the KNVB to manage the national team for the 1994 World Cup finals, but talks broke off at the last minute.[69]

Catalonia national team

As well as representing Catalonia on the pitch in 1976, Cruyff also managed the Catalonia national team from 2009 to 2013, leading the team to a victory over Argentina in his debut match.[70]

On 2 November 2009, Cruyff was named as manager of the Catalonia national team. It was his first managing job in 13 years.[71] On 22 December 2009, they played a friendly game against Argentina, which ended in a Catalonia win, 4–2 at Camp Nou. On 28 December 2010, Catalonia played a friendly against Honduras winning 4–0 at Estadi Olímpic Lluís Companys.[72] On 30 December 2011, Catalonia played Tunisia in a goalless draw at the Lluís Companys.[73] In their last game under Cruyff, on 2 January 2013, Catalonia drew with Nigeria at the Cornellà-El Prat, 1–1.[74]

Other football-related activities

As a technical advisor

Unofficial advisor to Barcelona president Joan Laporta

Later in his reign as Barcelona manager, Cruyff suffered a heart attack and was advised to quit coaching by his doctors. He left in 1996, and never took another top job, but his influence did not end there. Though he vowed never to coach again, he remained a vocal football critic and analyst. Cruyff's open support helped candidate Joan Laporta to victory in Barcelona's presidential elections. He continued to be an adviser for him, although he held no official post at Barcelona.[75][76] Back in an advisory capacity alongside Joan Laporta, he recommended the appointment of Frank Rijkaard in 2003. Again Barca was successful, winning back-to-back league titles and another Champions League crown in 2006.

After two relatively disappointing campaigns, Laporta survived a censure motion and an overhaul was needed. In summer 2008, Rijkaard left the club and even though José Mourinho was pushing for the job at Camp Nou, Cruyff chose Pep Guardiola. Many were quick to point to Guardiola's lack of coaching experience, but Cruyff said, "The biggest test for a coach at a team like Barça is the strength to make decisions and the ability to talk to the press, because they don't help and you have to manage that. After that, it's easy for those who know football. But there aren't many who know."[77]

On 26 March 2010, Cruyff was named honorary president of Barcelona in recognition of his contributions to the club as both a player and manager.[78] In July 2010, however, he was stripped of this title by new president Sandro Rosell.[79][80]

Return to Ajax as technical director

On 20 February 2008, in the wake of a major research on the ten-year-mismanagement, it was announced that Cruyff would be the new technical director at his boyhood club Ajax, his fourth stint with the Amsterdam club.[81] Cruyff announced in March that he was pulling out of his planned return to Ajax because of "professional difference of opinion" between him and Ajax's new manager, Marco van Basten. Van Basten said that Cruyff's plans were "going too fast", because he was "not so dissatisfied with how things are going now".[82]

On 11 February 2011, Cruyff returned to Ajax on an advisory basis after agreeing to become a member of one of three "sounding board groups".[83] After presenting his plans to reform the club, in particular to rejuvenate the youth academy, the Ajax board of advisors and the CEO resigned on 30 March 2011.[84] On 6 June 2011, he was appointed to the new Ajax board of advisors to implement his reform plans.[85][86]

The Ajax advisory board made a verbal agreement with Louis van Gaal to appoint him as the new CEO, without consulting Cruyff.[87] Cruyff, a fellow board member, took Ajax to court in an attempt to block the appointment.[88] The court overturned the appointment, saying that the board had "deliberately put Cruyff offside".[89] Due to the ongoing quarrel within the advisory board, Cruyff resigned on 10 April 2012, with Ajax stating that Cruyff will "remain involved with the implementation of his football vision within the club".[90]

Technical advisor for Chivas Guadalajara

Cruyff became a technical advisor for Mexican club Guadalajara in February 2012. Jorge Vergara, the owner of the club, made him the team's sport consultant in response to the losing record Guadalajara sustained in the last few months of 2011.[91] Although signed to a three-year contract, Cruyff's contract was terminated December 2012 after just nine months with the club. Guadalajara said that other members of the team's coaching staff would likely not be terminated.[92]

Ambassador for Belgium and the Netherlands joint bid to host the World Cup

In September 2009, Cruyff and Ruud Gullit were unveiled as ambassadors for the Belgium–Netherlands joint bid for the World Cup finals in 2018 or 2022 at the official launch in Eindhoven.[93]

Profile and legacy

Style of play: The total footballer

Regarded as one of the greatest players in history and as the greatest Dutch footballer ever,[3][5][6][94][95][96] throughout his career, Cruyff became synonymous with the playing style of "Total Football".[97][98][99] It is a system where a player who moves out of his position is replaced by another from his team, thus allowing the team to retain their intended organizational structure. In this fluid system, no footballer is fixed in their intended outfield role. The style was honed by Ajax coach Rinus Michels, with Cruyff serving as the on-field "conductor".[100][101] Space and the creation of it were central to the concept of Total Football. Ajax defender Barry Hulshoff, who played with Cruyff, explained how the team that won the European Cup in 1971, 1972 and 1973 worked it to their advantage: "We discussed space the whole time. Cruyff always talked about where people should run, where they should stand, where they should not be moving. It was all about making space and coming into space. It is a kind of architecture on the field. We always talked about speed of ball, space and time. Where is the most space? Where is the player who has the most time? That is where we have to play the ball. Every player had to understand the whole geometry of the whole pitch and the system as a whole."[102]

The team orchestrator, Cruyff was a creative playmaker with a gift for timing passes.[103] Nominally, he played centre-forward in this system and was a prolific goalscorer, but dropped deep to confuse his markers or moved to the wing to great effect.[104] In the 1974 World Cup final between West Germany and the Netherlands, from the kick-off, the Dutch monopolised ball possession. At the start of the move that led to the opening goal, Cruyff picked up the ball in his own half. The Dutch captain, who was nominally a centre-forward, was the deepest Dutch outfield player, and after a series of passes, he set off on a run from the centre circle into the West German box. Unable to stop Cruyff by fair means, Uli Hoeneß brought Cruyff down, conceding a penalty scored by Johan Neeskens. The first German to thus touch the ball was goalkeeper Sepp Maier picking the ball out of his own net.[105] This free centre-forward role in which Cruyff operated has retroactively been compared to the "false 9" position in contemporary football, by pundits such as Jamie Rainbow of World Soccer magazine.[106] Due to the way Cruyff played the game, he is still referred to as "the total footballer".[107]

Cruyff was known for his technical ability, speed, acceleration, dribbling and vision, possessing an awareness of his teammates' positions as an attack unfolded. "Football consists of different elements: technique, tactics and stamina", he told the journalists Henk van Dorp and Frits Barend, in one of the interviews collected in their book Ajax, Barcelona, Cruyff. "There are some people who might have better technique than me, and some may be fitter than me, but the main thing is tactics. With most players, tactics are missing. You can divide tactics into insight, trust and daring. In the tactical area, I think I just have more than most other players." On the concept of technique in football, Cruyff once said: "Technique is not being able to juggle a ball 1,000 times. Anyone can do that by practising. Then you can work in the circus. Technique is passing the ball with one touch, with the right speed, at the right foot of your team mate."[108]

Style of management and tactics

Cruyff is widely seen as a revolutionary figure in the history of Ajax, Barcelona, and the Netherlands. The offensive style of play Cruyff introduced at Barcelona later came to be known as tiki-taka—characterised by short passing and movement, working the ball through various channels, and maintaining possession—which was later adopted by the Euro 2008, 2010 FIFA World Cup and Euro 2012 winning Spain national football team.[109][110] As a manager, Cruyff's tactics were influenced by the Dutch total football system in which he played a part during his playing career under his former manager Michels.[111] Cruyff often used a fluid 3–4–3 formation at Barcelona, or occasionally the 4–3–3.[68][110] He often favoured technical players with good movement over physical players, and used his players in seemingly unorthodox roles on occasion.[110] For example, he made use of Spanish midfielder Pep Guardiola in a defensive midfield role as a deep-lying playmaker, who would dictate play in midfield through his passing; he would also occasionally drop deeper to act as an additional centre-back.[110][112] Cruyff also deployed Danish playmaker Michael Laudrup in a free centre-forward role, due to his mobility, positioning, passing, and tendency to be involved in the build-up of attacking plays and create chances for teammates; Laudrup would often drop deep into midfield, which would disorient opposing defenders, allowing other midfielders, or offensive wingers, such as Stoichkov, to exploit the space he created, and get into good attacking positions from which they could shoot on goal. This role has retroactively been likened by pundits to the modern "false 9" role, and has also been compared to Cruyff's own playing position. Cruyff did also use a genuine striker at times, in particular when Romário joined the club.[110][113][106] Defensively, his teams made use of heavy pressing, a high defensive line, and the offside trap, and relied on the positioning of his players to recover the ball quickly, maintain possession, and reduce the possibility of facing opposing counter-attacks; as such, Cruyff's philosophy was based on defending by attacking.[110][68][114] He also used Sergi and Ferrer as inverted full-backs, who moved inside to occupy central areas of the pitch, flanking an offensive sweeper – usually Ronald Koeman – who could carry the ball, start attacks or switch the play from the back,[110][115][116] while he also favoured goalkeepers who were comfortable with the ball at their feet, and equally capable of building plays with their passing.[110][117][118] Despite Cruyff's reputation as one of the greatest managers of all time,[4][5][6][7][8][94][119] former Milan and Italy manager Arrigo Sacchi was critical of Cruyff in 2011, however, due to the fact that he did not pay as much attention to the defensive aspect of the game as he did to the offensive side.[120]

Win-with-style philosophy

Winning is just one day, a reputation can last a lifetime. Winning is an important thing, but to have your own style, to have people copy you, to admire you, that is the greatest gift.

— Johan Cruyff[121]

Cruyff always considered the aesthetic and moral aspects of the game; it was not just about winning, but about winning with the ‘right’ style and in the ‘right’ way. He also always spoke highly of the entertainment value of the game. The beautiful game, for him, was as much about entertainment and joy as results. In the thinking of Cruyff, victory was only truly meaningful when it could fully capture the minds and hearts of competitors and spectators. As he once noted, "Quality without results is pointless. Results without quality is boring,".[122] For Cruyff, choosing a ’right’ style of play to win was even more important than winning itself.[123][124] Cruyff always believed in simplicity, seeing simplicity and beauty as inseparable. "Simple football is the most beautiful. But playing simple football is the hardest thing", as Cruyff once summed up his fundamental philosophy.[125] "How often do you see a pass of forty meters when twenty meters is enough?... To play well, you need good players, but a good player almost always has the problem of a lack of efficiency. He always wants to do things prettier than strictly necessary."[126]

Cruyff also perfected a feint now known as the "Cruyff Turn".[104] The feint is an example of the simplicity in Cruyff's football philosophy. It was neither carried out to embarrass the opponent nor to excite the watching crowd, but because Cruyff estimated that it was the simplest method (in terms of effort and risk versus expected result) to beat his opponent. Cruyff looked to pass or cross the ball, then, instead of kicking it, he dragged the ball behind his planted foot with the inside of his other foot, turned through 180 degrees, and accelerated away.[127] As Swedish defender Jan Olsson (a "victim" of the Cruyff Turn at the 1974 World Cup) recalled, "I played 18 years in top football and seventeen times for Sweden but that moment against Cruyff was the proudest moment of my career. I thought I'd win the ball for sure, but he tricked me. I was not humiliated. I had no chance. Cruyff was a genius."[128]

Like Dutch football in general until the mid-1960s, Cruyff's early playing career was considerably influenced by coaching philosophy of British coaches such as Vic Buckingham.[129][130]

The mind-body duality always played an important role in his footballing philosophy. In Cruyff's words, quoted in Dennis Bergkamp's autobiography Stillness and Speed: My Story, "...Because you play football with your head, and your legs are there to help you. If you don't use your head, using your feet won't be sufficient. Why does a player have to chase the ball? Because he started running too late. You have to pay attention, use your brain and find the right position. If you get to the ball late, it means you chose the wrong position. Bergkamp was never late."[131] For Cruyff, football was an artistic-oriented mind-body game instead of an athletic-oriented physical competition. As he put it, "Every trainer talks about movement, about running a lot. I say don't run so much. Football is a game you play with your brain. You have to be in the right place at the right moment, not too early, not too late."[102]

The creativity was always the key element in his footballing philosophy, both as a player and as a manager. Cruyff once compared his more intuitive and individualistic approach with Louis van Gaal's more mechanized and rigid coaching style, "Van Gaal has a good vision on football. But it's not mine. He wants to gel winning teams and has a militaristic way of working with his tactics. I don't. I want individuals to think for themselves and take the decision on the pitch that is best for the situation... I don't have anything against computers, but you judge football players intuitively and with your heart. On the basis of the criteria which are now in use at Ajax [recommended by Van Gaal] I would have failed the test. When I was 15, I could barely kick the ball 15 metres with my left and with the right maybe 20 metres. I would not have been able to take a corner. Besides, I was physically weak and relatively slow. My two qualities were great technique and insight, which happen to be two things you cannot measure with a computer."[132]

Cruyff's favourite World XI

In his posthumously released autobiography My Turn: The Autobiography,[133] Cruyff reveals his dream all-time XI in his favourite 3–4–3/4–3–3 formation. Cruyff's side (in the 3–4–3 diamond formation) reads as follows: Lev Yashin (goalkeeper); Ruud Krol (full back/wing-back), Franz Beckenbauer (central defender/libero), Carlos Alberto (full-back/wing-back); Pep Guardiola (holding midfielder/midfield anchor), Bobby Charlton, Alfredo Di Stéfano, Diego Maradona (playmaker/attacking midfielder/second striker); Piet Keizer (winger), Garrincha (winger), and Pelé (centre-forward/striker). For humility, Cruyff did not put himself in there, but there is a spot for his pupil, Pep Guardiola and his former teammates, Ruud Krol and Piet Keizer. It's a typically attacking line-up but Cruyff explains the selection in detail. "For the ideal squad, I also try and find a formula in which talent is used to the maximum in every case", notes Cruyff. "The qualities of one player have to complement the qualities of another."[134][135]

Cruyff's 14 rules

In his autobiography, Cruyff explained why he made a set of 14 basic rules, which are displayed at every Cruyff Court in the world: "I read an article once about the building of the pyramids in Egypt. It turns out that some of the numbers coincide completely with natural laws – the position of the moon at certain times and so on. And it makes you think: how is it possible that those ancient people built something so scientifically complex? They must have had something that we don't, even though we always think that we're a lot more advanced than they were. Take Rembrandt and van Gogh: who can match them today? When I think that way, I'm increasingly convinced that everything is actually possible. If they managed to do the impossible nearly five thousand years ago, why can't we do it today? That applies equally to football, but also to something like the Cruyff Courts and school sports grounds. My fourteen rules are set out for every court and every school sports ground to follow. They are there to teach young people that sports and games can also be translated into everyday life."[133]

And he listed his 14 basic rules that include:

- Team player – 'To accomplish things, you have to do them together.';

- Responsibility – 'Take care of things as if they were your own.';

- Respect – 'Respect one another.';

- Integration – 'Involve others in your activities.';

- Initiative – 'Dare to try something new.';

- Coaching – 'Always help each other within a team.';

- Personality – 'Be yourself.';

- Social involvement – 'Interaction is crucial, both in sport and in life.';

- Technique – 'Know the basics.';

- Tactics – 'Know what to do.';

- Development – 'Sport strengthens body and soul.';

- Learning – 'Try to learn something new every day.';

- Play together – 'An essential part of any game.';

- Creativity – 'Bring beauty to the sport.'[133]

Named after Cruyff

- Cruyff turn (known as "Cruijff turn" in Dutch), a dribbling trick perfected by Cruyff. The trick was famously employed by Cruyff during the 1974 World Cup.[128]

- Johan Cruyff Shield (Johan Cruijff Schaal in Dutch), a football trophy in the Netherlands, also referred to as the Dutch Super Cup.

- Johan Cruyff Award or Dutch Football Talent of the Year (Dutch: Nederlands Voetbal Talent van het Jaar), the title has been awarded in the Netherlands since 1984 for footballers under 21. The award Dutch Football Talent of the Year was replaced by the Johan Cruyff Trophy (Johan Cruijff Prijs in Dutch) in 2003.

- 14282 Cruijff, the asteroid (minor planet) was named after Cruyff. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially ratified the naming of Cruijff on 23 September 2010.

- Johan Cruyff Institute, an educational institution, founded by Johan Cruyff, aimed at educating athletes, sport and business professionals in the field of sport management, sport marketing, football business, sponsorship and coaching through a network that currently has five Johan Cruyff Institute (postgraduate and executive education), three Johan Cruyff Academy (graduate education) and five Johan Cruyff College (vocational training).

- Johan Cruyff Foundation, founded in 1997 from the wish of Cruyff to give children the opportunity to play and be active.

- Johan Cruyff Academy, offers elite athletes an opportunity to balance sports with a four-year Bachelor of Business Administration programme in Sport Marketing, a learning track of Commercial Economics. There are Johan Cruyff Academy in Amsterdam, Groningen and Tilburg. These Johan Cruyff Academy are part of Dutch universities of applied science.

- Johan Cruyff College, offers elite athletes from all kinds of sports an opportunity to balance sport with vocational education. The programmes of the Johan Cruyff College are designed for students who practice sports at the highest levels in The Netherlands, and are delivered in Dutch. There are five Johan Cruyff College in The Netherlands: Amsterdam, Enschede, Groningen, Nijmegen and Roosendaal. Each Johan Cruyff College is part of a Regional Education Centre or ROC, academic centres that are administered by the Dutch government.

- Cruyff Courts, smaller sized football fields suitable for seven-a-side game. A Cruyff Court is a modern alternative to the ancient green public playground, which one could find in a lot of neighbourhoods and districts, but that over the years has been sacrificed due to urbanisation and expansion.[136]

- Cruijffiaans, the name given to the way of speaking, or a collection of sayings, made famous by Cruyff, particularly "one-liners that hover somewhere between the brilliant and the banal".

- Cruyffista (mainly in Spain), a follower/supporter of Cruyff's views (principles) on football development philosophy and sports culture.[137][124]

- Johan Cruyff Stadium (Estadi Johan Cruyff in Catalan), FC Barcelona's newly constructed stadium is named after Cruyff.

- Johan Cruyff Arena (Johan Cruijff Arena in Dutch), previously known as the Amsterdam Arena.

In popular culture

In 2018, Cruyff was added as an icon to the Ultimate Team in EA Sports' FIFA video game FIFA 19, receiving a 94 rating.[138] British sportswriter David Winner's 2000 book on Dutch football, Brilliant Orange, mentions Cruyff frequently. In the book, Dutch football's ideas (in particular Cruyff's) effectively related to the use of space in Dutch painting and Dutch architecture.

In 1976, the Italian-language documentary film Il profeta del gol was directed by Sandro Ciotti. The documentary narrates the successes of Johan Cruyff's football career in the 1970s. In 2004, the documentary film Johan Cruijff – En un momento dado ("Johan Cruijff – At Any Given Moment") was made by Ramon Gieling and charts the years Cruyff spent at Barcelona, the club where he had the most profound effect in both a footballing and cultural sense. In 2014, the Catalan-language documentary film L'últim partit: 40 anys de Johan Cruyff a Catalunya was directed by Jordi Marcos, celebrating 40 years since Johan Cruyff signed for Barcelona in August 1973.

British rock band The Hours recorded a song called "Love You More" in 2007. In it lead singer Antony Genn described his partner as "Better than Elvis in his '68 comeback, Better than Cruyff in '74..", In an interview with German daily Sueddeutsche Zeitung in 2008, when German Chancellor Angela Merkel was discussing the upcoming Euro 2008, she praised Cruyff's performance at the 1974 World Cup: "Cruyff really impressed me. I think I wasn't the only one in Europe."[139] Cruyff stood out at the 1974 World Cup in West Germany which Merkel watched from her then home country East Germany.[140]

In the Netherlands, and to some extent Spain, Cruyff is famous for his one-liners that usually hover between brilliant insight and the blatantly obvious. They are famous for their Amsterdam dialect and incorrect grammar, and often feature tautologies and paradoxes.[141] In Spain, his most famous statement is "En un momento dado" ("In any given moment"). The quote has been used for the title of a 2004 documentary about Cruyff's life: Johan Cruijff – En un momento dado. In the Netherlands, his most famous one-liner is "Ieder nadeel heb z'n voordeel" ("Every disadvantage has its advantage") and his way of expressing himself has been dubbed "Cruijffiaans". Cruyff rarely limited himself to a single line though, and in a comparison with the equally oracular but reserved football manager Rinus Michels, Kees Fens equated Cruyff's monologues to experimental prose, "without a subject, only an attempt to drop words in a sea of uncertainty ... there is no full stop".[141]

He had a small hit (number 21 in the charts) in the Netherlands with "Oei Oei Oei (Dat Was Me Weer Een Loei)". Upon arriving in Barcelona, the Spanish branch of Polydor decided to release the single in Spain as well, where it was rather popular.[142]

Cruyff suffered a heart attack (like his father who died of a heart attack when he was 12) in his early forties. He used to smoke 20 cigarettes a day prior to undergoing double heart bypass surgery in 1991 while he was the coach of Barcelona. Cruyff was forced to immediately give up smoking, and he made an anti-smoking advertisement for the Catalan Department of Health. In the TV spot, Cruyff is dressed like a manager in a long trench coat combined with collared shirt and necktie. He performed keepy-uppies with a pack of cigarettes by juggling it 16 times – using feet, thighs, knees, heel, chest, shoulder, and head like holding up a ball – before volleying it away. Throughout the commercial he speaks in Catalan about the dangers of smoking.[143]

In November 2003, Cruyff invoked legal proceedings against the publisher Tirion Uitgevers, over its photo book Johan Cruyff de Ajacied ("Johan Cruijff the Ajax player"), which used photographs by Guus de Jong. Cruyff was working on another book, also using De Jong's photographs, and claimed unsuccessfully that Tirion's book violated his trademark and portrait rights.

In 2004, a public poll in the Netherlands to determine the greatest Dutchman ("De Grootste Nederlander") named Cruyff the 6th-greatest Dutchman of all time, with Cruyff finishing above Rembrandt (9th) and Vincent van Gogh (10th).[144] In 2010, the asteroid (minor planet) 14282 Cruijff (2097 P-L) [de] was named after him. The International Astronomical Union (IAU) officially ratified the naming of Cruijff on 23 September 2010. After Josef Bican and Ferenc Puskás, Cruyff is the third football player to have an asteroid named after him.[145][146]

Nicknames

There were many nicknames Cruyff had in the Netherlands and Spain, including "Jopie", "Nummer 14" (Number 14),[147] "Het orakel van Betondorp" (the prophet of Betondorp), "El Salvador" (The Saviour), and "El Flaco" (The Skinny One). One of his best known nicknames was "El Salvador" or "The Saviour", a nickname he received during the 1973–74 season and again in 1988, when he helped terminate crisis eras in Barça's history.[60][121][148] However, contrary to popular belief, the nickname "El Salvador" is a Dutch rather than Spanish invention.[149]

Outside football

Hobbies

Outside football, Cruyff's favourite sport (and hobby) was golf.[150][151]

In the 1970s, he loved to collect cars. In Sandro Ciotti's documentary film Il Profeta del gol (1976), Cruyff said, "I like to drive for the 20 km that separate the training camp from my house, it relaxes me. I love the cars."[152]

Business ventures

In 1979, Cruyff was reaching the twilight of his career in Barcelona. He began to imagine creating a range of footwear himself to challenge the technical and luxury qualities of those on the market beforehand. After a few years of trying and failing to encourage big sportswear brands to take his idea seriously, after all this was quite an unusual ambition of a professional sportsman at the time. Eventually he combined with his close friend, Italian designer Emilio Lazzarini, and using his knowledge he set out to create a technical shoe which managed to balance functionality with elegance. Initially the range was filled with "luxury" indoor football shoes, but they quickly became used as a fashion shoe due to their attractive appearance. And so Cruyff Classics brand was born.[153][154]

Writing

Cruyff is the author/co-author of several books (in Dutch and Spanish) about his football career, in particular his principles and view about the football world. He also wrote his weekly columns for El Periódico (Barcelona-based newspaper) and De Telegraaf (Amsterdam-based newspaper).[155]

Cruyff was multilingual; British football writer Brian Glanville wrote: "his intelligence off the field as well as on it was quite remarkable. How well I remember seeing Cruyff surrounded by journalists from all over the world in 1978 to whose questions he replied almost casually in a multiplicity of languages. Not only Dutch, but English, French, Spanish and German."[156]

Philanthropy

The Johan Cruyff Foundation[157] has provided over 200 Cruyff Courts in 22 countries, including Israel, Malaysia, Japan, United States and Mexico, for children of all backgrounds to play street football together. UEFA praised the foundation for its positive effect on young people, and Cruyff received the UEFA Grassroots Award on the opening of the 100th court in late 2009.[158] In 1999, he founded the Johan Cruyff Institute with a programme for 35 athletes as part of the Johan Cruyff University of Amsterdam and has since become a global network.[159]

Cuyff was also an ambassador of the Postcode Lottery Group, which establishes and manages charitable lotteries worldwide to raise funds for social organisations.[160]

Personality

Born in the heavily damaged post–World War II Netherlands, Cruyff came from a humble background and lost his father as a child. This had a great influence on his future career and character. He was renowned for his strong personality. His character, both in and beyond the footballing world, was much described as the complicated combination of an idealist,[161] individualist, libertarian, collectivist, romantic, purist, pragmatist, rebel,[162] and even despot.[163] Dutch sportswriter Johan Derksen, a close friend of Cruyff, once said of him, "Johan is absolutely religious, though he never goes to church."[164]

In August 1973, Ajax players voted for Piet Keizer to be the team's captain in a secret ballot, ahead of Cruyff. And Cruyff decided his time in Amsterdam had come to an end. He joined Barcelona just weeks later, two years before the Spanish dictator Francisco Franco died, maintaining to the European press corps en route that he chose Barcelona over rivals Real Madrid because he could never join a club "associated with Franco".[165] As he recalled in a documentary on TV3 channel, "I remember my move to Spain was quite controversial. ... The president of Ajax wanted to sell me to Real Madrid, ... Barcelona weren't at the same level as Madrid football wise, but it was a challenge to play for a Catalan club. Barcelona was more than a club."[166] At the end of the 1982–83 season, Ajax decided not to offer Cruyff a new contract. This angered Cruyff and he responded by signing for Ajax's archrivals Feyenoord. Cruyff's season at Feyenoord was a successful one in which the club won the Eredivisie for the first time in a decade, part of a league and KNVB Cup double.[49]

Cruyff's strong personality played a role in the struggle between Puma and Adidas, the two rival brands that were born from the divisions between the two Dassler brothers.[152] Cruyff was a fan of Puma's King boots and by 1974 had signed a sponsorship deal with the German sportswear and equipment supplier. At the 1974 World Cup, he was under contract with Puma in a deal that prohibited him from promoting other sports brands. As the tournament approached, Cruyff flatly refused to wear Adidas's trademark three black stripes on his No. 14 jersey. The Netherlands national football association had little choice but to honour the wishes of their best player, and Dutch officials eventually persuaded Adidas to design a separate jersey just for Cruyff, with just two stripes running along the sleeves.[167][168]

Jersey number 14

Until the 1990s, players did not have fixed numbering—except in some short competitions like the World Cup or European Championship where players were given a designated number. The starting players usually wore jerseys from 1 to 11 and the substitutes from 12 to 16. Cruyff's usual number was 9.[169]

On 30 October 1970, Cruyff was coming back from a long-term injury to play Ajax's rivals PSV. However, in the locker room before the match, teammate Gerrie Muhren could not find his number 7 jersey. Cruyff offered his shirt to Muhren and went to the basket to pick another one at random. It happened to be the number 14.[169] Ajax won 1–0 and Cruyff suggested they keep the same numbers to the following game—according to Muhren, in an interview to Voetbal International, it was a form to challenge the Dutch Football Association.[169] From then on, Cruyff kept using the number 14 for Ajax and Netherlands national team when he was allowed to.[11][169]

In the 1974 FIFA World Cup, Netherlands' head coach Rinus Michels wanted his squad to wear numbers alphabetically. As Cruyff was the first player on the roster, he would be number 1, but he refused and insisted on wearing his lucky number 14.[169] Forward Ruud Geels ended up with the number 1 shirt while goalkeeper Jan Jongbloed played as the number 8.

Although the number 14 had become a trademark for Cruyff, he could be seen wearing his old number 9 on other occasions, like during most of his career for FC Barcelona, because the league demanded starting players were numbered 1 to 11,[170] or for Netherlands in the 1976 European Championship. In 2007, Ajax retired Cruyff's number 14.[169]

Relations with others

Cruyff remained a controversial figure throughout his life. His relationships with Ajax, Barça, and KNVB (Royal Dutch Football Association) were turbulent for some time, especially in his later years. In his native Netherlands, there was always a love–hate relationship between Cruyff and his fellow countrymen.[171] A dispute with goalkeeper Jan van Beveren resulted in van Beveren being dropped from the Dutch national side, after Cruyff refused to play if he was picked.[172] There was a long-standing feud between Cruyff and Louis van Gaal, though never confirmed publicly by both sides.[173] He also often criticised José Mourinho for his defensive-based coaching philosophy, stated, "José Mourinho is a negative coach. He only cares about the result and does not care much for good football." As David Winner notes, "Cruyff has had many enemies and critics over the years."[174] He has been accused of being arrogant, greedy,[171] intolerant, despotic, "too idealistic, too stubborn, insufficiently interested in defending and simply too difficult a personality. He loves an argument, and his conflict-model method of working can be bruising."[174] And Winner concludes that, "With his belief in the "conflict model" – the idea that you got the best out of people by provoking fights and thereby raising levels of excitement and adrenaline – Cruyff made enemies almost as easily as he generated delight. Battles with club presidents and teammates led to ruptures, especially at Ajax and Barcelona, the two clubs that defined his career."[175]

Criticism

Cruyff was also well known for his vocal criticism and uncompromising attitude. A perfectionist, he always had a strong opinion about things and was loyal to his principles even more than anything else in the football world.[176] As an outspoken and critical visionary, he strongly criticized the Netherlands' style of play at the 2010 World Cup. "Who am I supporting? I am Dutch but I support the football that Spain is playing. Spain's style is the style of Barcelona... Spain, a replica of Barça, is the best publicity for football", Cruyff wrote in his weekly column for the Barcelona-based newspaper El Periódico, prior to the final match.[177]

Until the early 2010s, Barcelona had mounting debts, built up over the previous few seasons, a situation that forced the club to push through an emergency bailout loan of €150 million. The Qatar Foundation, run by Sheikha Mozah, became the first shirt sponsor in Barcelona's 111-year history. The club had previously used UNICEF's logo on the front of its shirts.[178] In 2011, incoming Barcelona president Sandro Rosell agreed the deal for a period of five seasons, with the club receiving €30 million each year, starting on 1 July 2011 and running until 30 June 2016, plus bonuses for trophies won that could total €5m.[179] Writing in his El Periódico column, Cruyff slammed the deal, "We are a unique club in the world, no one has kept their jersey intact throughout their history, yet have remained as competitive as they come... We have sold this uniqueness for about six percent of our budget. I understand that we are currently losing more than we are earning. However, by selling the shirt it shows me that we are not being creative, and that we have become vulgar."[180]

In an interview with The Guardian's Donald McRae in 2014, Cruyff spoke about football's lost values and how money had eroded the game's purity, "Football is now all about money. There are problems with the values within the game. This is sad because football is the most beautiful game. We can play it in the street. We can play it everywhere. Everyone can play it whether you're tall or small, fat or thin. But those values are being lost. We have to bring them back."[181]

Personal life

At the wedding of Ajax teammate Piet Keizer, on 13 June 1967, Cruyff met his future wife, Diana Margaretha "Danny" Coster (born 1949). They started dating, and on 2 December 1968, at the age of 21, he married Danny. Her father was Dutch businessman Cor Coster who also happened to be Cruyff's agent. He was also credited with engineering Cruyff's move to FC Barcelona in 1973. The marriage is said to have been happy for almost 50 years.[182] Contrary to his well-known strong personality and superstar status, Cruyff led a relatively quiet private life beyond the world of football.[183] A highly principled, strong-minded and devoted family man, Cruyff's football career, both as a player and as a manager, was considerably influenced by his family, in particular his wife Danny.[184][185] He and Danny had three children together: Chantal (16 November 1970), Susila (27 January 1972), and Jordi (9 February 1974). The family lived in Barcelona from 1973, with a six-year interruption from December 1981 to January 1988 when they lived in Vinkeveen.[186]

In 1977, Cruyff announced his decision to retire from international football at the age of 30, despite still being lean and wiry, after helping the country qualify for the 1978 World Cup.[187] This move, shrouded in mystery and met with disbelief back in late 1977, was only finally stripped of its mystique in 2008, when Cruyff explained his decision in an interview with Catalunya Ràdio. It was while still living in Barcelona as a player in late 1977, Cruyff and his family became the victims of an armed attacker who forced his way into his flat in Barcelona.[188] The man who was then the ultimate football superstar was confronted with the choice between family values and a highly promising World Cup glory at the end of his international career. In the interview with Catalunya Ràdio, he said that the attempted kidnap was the reason he decided not to go to the World Cup in Argentina in 1978. As he recalled, "You should know that I had problems at the end of my career as a player here and I don't know if you know that someone [put] a rifle at my head and tied me up and tied up my wife in front of the children at our flat in Barcelona. The children were going to school accompanied by the police. The police slept in our house for three or four months. I was going to matches with a bodyguard. All these things change your point of view towards many things. There are moments in life in which there are other values. We wanted to stop this and be a little more sensible. It was the moment to leave football and I couldn't play in the World Cup after this."[189]

Cruyff named his third child after the patron saint of Catalonia, St Jordi, commonly known in English as Saint George of Lydda. This was seen as a provocative gesture towards the then Spanish dictator General Franco, who had made all symbols of Catalan nationalism illegal. Cruyff had to fly his son back to the Netherlands to register his birth as the name "Jordi" had been banned by the Spanish authorities. Cruyff's decision to go to such great lengths to support Catalan nationalism is part of the reason he is a hero to Barcelona supporters and Catalan nationalists.[190]

Jordi Cruyff played for teams such as Barcelona (while father Johan was manager), Manchester United, Alavés and Espanyol. He wore "Jordi" on his shirt to distinguish himself from his father, which also reflects the common Spanish practice of referring to players by given names alone or by nicknames. His grandson, Jesjua Angoy, played for Dayton Dutch Lions. Pep Guardiola, Ronald Koeman, and Joan Laporta were among Cruyff's closest friends.[191] Estelle Cruijff, a niece of Cruyff, was married to Ruud Gullit for 12 years (2000–2012),[192][193] and their son Maxim Gullit plays for Cambuur.[194]

Religious views

Cruyff once described himself as "not religious" and criticised the practices of devoutly Catholic Spanish players: "In Spain all 22 players make the sign of the cross before a game; if it worked, every game would be a tie."[195] That widely quoted statement earned him a place on lists of the world's top atheist athletes. But in the 1990s, Cruyff told the Dutch Catholic radio station RKK/KRO that as a child he attended Sunday school, where he was taught about the Bible, and that while he did not go to church as an adult, he believed "there's something there."[196] The Dutch evangelical broadcaster EO posted an interview conducted before Cruyff's death with his friend Johan Derksen, the editor-in-chief of Voetbal International magazine. "People don't know the real Johan Cruyff", Derksen said. "I have on occasion had beautiful conversations with him about faith, because we both went to the same kind of schools and learned about the Bible. And it stays with you."[197][198] Cruyff also expressed his faith in God in an interview with Hanneke Groenteman on Sterren op het Doek.[199]

Quotes

- "Every trainer talks about movement, about running a lot. I say don't run so much. Football is a game you play with your brain. You have to be in the right place at the right moment, not too early, not too late."[102]

- "In my teams, the goalie is the first attacker, and the striker the first defender."[200]

- "Every disadvantage has its advantage."[174]

- "If you can't win, make sure you don't lose."[174]

- "Quality without results is pointless. Results without quality is boring."[122]

- "Winning is an important thing, but to have your own style, to have people copy you, to admire you, that is the greatest gift."[121]

- "Playing football is very simple but playing simple football is the hardest thing there is."[201]

Illness, death and tributes

He has enriched and personified our football. He was an icon of the Netherlands. Johan Cruijff belonged to all of us.

Cruyff had always been a heavy smoker from his boyhood until he underwent an emergency bypass operation in 1991. After giving up smoking following the surgery, he took to sucking lollipops when watching games.[203] He featured in a Catalan health department advertisement, saying, "Football has given me everything in life, tobacco almost took it all away."[203][204] After more heart trouble in 1997, he vowed never to coach again (until 2009), though he remained a vocal football critic and analyst.[205]

In October 2015 he was diagnosed with lung cancer.[206] After the news broke, tributes poured in for Cruyff, with all Eredivisie games featuring a round of applause on 14 minutes, Cruyff's former shirt number. Ahead of their league game against Eibar at the Camp Nou (25 October 2015), Barcelona players showed their support for Cruyff by wearing orange T-shirts bearing the words "Ànims Johan" (Catalan for "Get well soon Johan"). Writing in his weekly De Telegraaf column, Cruyff admitted, "Often the media are an additional tax, but the last week that has been different. The way in which a reply is posted via a variety of media in my situation, was emotional and heartwarming. I am extremely proud of the appreciation shown by all responses." On his condition, Cruyff added, "Meanwhile, we have to wait. It's really annoying that it has been leaked so quickly, because the only thing I know now is that I have lung cancer. No more. Because the investigation is ongoing."[207]

In mid-February 2016, he stated that he had been responding well to chemotherapy and was "winning" his cancer battle.[208][209] On 2 March 2016, he was in attendance on the second day of winter testing at the Circuit de Catalunya just outside Barcelona and visited Dutch Formula One driver Max Verstappen. Cruyff appeared to be in good spirits and it is believed this was the last time he was seen in public.[210][211][212] On the morning of 24 March 2016, in a clinic in Barcelona, Cruyff died at the age of 68, surrounded by his wife, children, and grandchildren.[213] His lung cancer had metastasized to his brain and a week before his death he had begun to lose his ability to speak as well as movement on his left side. He was cremated in Barcelona within 24 hours[214] of his death. A private ceremony was held, attended only by his wife, children and grandchildren.[215][216][217]

Within a week of his death, several people (including players and managers) and organisations (including clubs) paid tribute to him, especially via social media.[218][219][220][221] Thousands of Barcelona fans passed through the memorial to Cruyff, opened inside the Camp Nou stadium, to pay tribute.[222][223][224] Former Barcelona president Sandro Rosell, who did not have a good relationship with Cruyff, was among the early visitors to the memorial.[225] Real Madrid president Florentino Pérez led a Real Madrid delegation to the memorial, including former players Emilio Butragueño and Amancio Amaro.[226]

A friendly match between the Netherlands and France was held on the day after Cruyff's death. The play (at the Amsterdam Arena) was stopped in the 14th minute as players, staff, and supporters gave a minute's applause for Cruyff, who wore the number 14 shirt for his country. Mascots from both teams took to the pitch wearing Netherlands national team shirts adorned with Cruyff's number 14 on the front, while there were numerous banners in the spectators' stands bearing the simple message, "Johan Bedankt" ("Thank you Johan").[227]

Ahead of the El Clásico against Real Madrid (2 April 2016),[228] Barcelona announced plans for five special tributes to Cruyff:

- 1.) A mosaic formed by the 90,000 fans inside Camp Nou carrying the words 'Gràcies Johan' (Catalan for 'Thank you, Johan')

- 2.) The words 'Gràcies Johan' would replace the World Club champions badge on the front of the Barcelona players' shirts

- 3.) Children wearing T-shirts with the words 'Gràcies Johan' would accompany Barça's and Madrid's players on to the pitch at the beginning of the game. The logo of the Johan Cruyff Foundation would feature on the back of the T-shirts

- 4.) The presence of all eight living (past and present) Barcelona presidents: Agustí Montal i Costa, Raimon Carrasco, Josep Lluís Núñez, Joan Gaspart, Enric Reyna, Joan Laporta, Sandro Rosell and Josep Maria Bartomeu

- 5.) A commemorative video honouring Cruyff's life would be shown on the big screens at Camp Nou stadium.[229][230] An open letter signed by Barcelona's eight current and previous presidents read: "With Cruyff we began to play differently, breaking new ground and innovating. With him, both as a player and coach, we established our own style on the field, what is traditionally known as 'total football,' the Barça style everyone admires. The arrival of Cruyff altered the history of Barça. He contributed decisively to a change of mentality. He got us to keep our heads up and to see that no opponent was invincible, that we could attain what we were aiming for. Cruyff was an icon who explained, better than anyone, that Barça is more than a club. ... Without Cruyff's unabashed and non-conformist spirit, we quite possibly wouldn't have become the greatest club in the world."[231][232]

Career statistics

Club

| Club | Season | League | Cup[a] | Continental[b] | Other[c] | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Division | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | Apps | Goals | ||

| Ajax | 1964–65 | Eredivisie | 10 | 4 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 10 | 4 | ||

| 1965–66 | Eredivisie | 19 | 16 | 4 | 9 | — | — | 23 | 25 | |||

| 1966–67 | Eredivisie | 30 | 33 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 3 | — | 41 | 41 | ||

| 1967–68 | Eredivisie | 33 | 27 | 5 | 6 | 2 | 1 | — | 40 | 34 | ||

| 1968–69 | Eredivisie | 29 | 24 | 3 | 3 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 43 | 34 | |

| 1969–70 | Eredivisie | 33 | 23 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 4 | — | 46 | 33 | ||

| 1970–71 | Eredivisie | 25 | 21 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 1 | — | 37 | 27 | ||

| 1971–72 | Eredivisie | 32 | 25 | 4 | 3 | 9 | 5 | — | 45 | 33 | ||

| 1972–73 | Eredivisie | 32 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 42 | 23 | |

| 1973–74 | Eredivisie | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 | |

| Total | 245 | 193 | 32 | 37 | 47 | 23 | 5 | 4 | 329 | 257 | ||

| Barcelona | 1973–74 | La Liga | 26 | 16 | 12 | 8 | 0 | 0 | — | 38 | 24 | |

| 1974–75 | La Liga | 30 | 7 | 12 | 7 | 8 | 0 | — | 50 | 14 | ||

| 1975–76 | La Liga | 29 | 6 | 10 | 3 | 9 | 2 | — | 48 | 11 | ||

| 1976–77 | La Liga | 30 | 14 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 5 | — | 46 | 25 | ||

| 1977–78 | La Liga | 28 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 5 | — | 45 | 11 | ||

| Total | 143 | 48 | 50 | 25 | 34 | 12 | — | 227 | 85 | |||

| Los Angeles Aztecs | 1979 | NASL | 22 | 14 | — | — | 4 | 1 | 26 | 15 | ||

| Washington Diplomats | 1980 | NASL | 24 | 10 | — | — | 2 | 0 | 26 | 10 | ||

| Levante | 1980–81 | Segunda División | 10 | 2 | 0 | 0 | — | — | 10 | 2 | ||

| Washington Diplomats | 1981 | NASL | 5 | 2 | — | — | — | 5 | 2 | |||

| Ajax | 1981–82 | Eredivisie | 15 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | — | 16 | 7 | |

| 1982–83 | Eredivisie | 21 | 7 | 7 | 2 | 2 | 0 | — | 30 | 9 | ||

| Total | 36 | 14 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 0 | — | 46 | 16 | |||

| Feyenoord | 1983–84 | Eredivisie | 33 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 1 | — | 44 | 13 | |

| Career total | 518 | 294 | 97 | 65 | 87 | 36 | 11 | 5 | 713 | 400 | ||

- ^ Appearances in KNVB Cup and Copa del Rey

- ^ Appearances in European Cup and Fairs Cup

- ^ Appearances in Intertoto Cup, UEFA Super Cup, Intercontinental Cup and NASL Play Offs

International

| National team | Year | Apps | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Netherlands | 1966 | 2 | 1 |

| 1967 | 3 | 1 | |

| 1968 | 1 | 0 | |

| 1969 | 3 | 1 | |

| 1970 | 2 | 2 | |

| 1971 | 4 | 6 | |

| 1972 | 5 | 5 | |

| 1973 | 6 | 6 | |

| 1974 | 12 | 8 | |

| 1975 | 2 | 0 | |

| 1976 | 4 | 2 | |

| 1977 | 4 | 1 | |

| Total | 48 | 33 | |

- Scores and results list the Netherlands' goal tally first, score column indicates score after each Cruyff goal.

| No. | Date | Venue | Opponent | Score | Result | Competition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 September 1966 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 2–0 | 2–2 | UEFA Euro 1968 qualifying | |

| 2 | 13 September 1967 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 1–0 | 1–0 | ||

| 3 | 26 March 1969 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 1–0 | 4–0 | 1970 FIFA World Cup qualification | |

| 4 | 2 December 1970 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 1–0 | 2–0 | Friendly | |

| 5 | 2–0 | |||||

| 6 | 24 February 1971 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 3–0 | 6–0 | UEFA Euro 1972 qualifying | |

| 7 | 4–0 | |||||

| 8 | 17 November 1971 | Eindhoven, Netherlands | 1–0 | 8–0 | ||

| 9 | 7–0 | |||||

| 10 | 8–0 | |||||

| 11 | 1 December 1971 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 1–0 | 2–1 | Friendly | |

| 12 | 16 February 1972 | Athens, Greece | 3–0 | 5–0 | ||

| 13 | 5–0 | |||||

| 14 | 30 August 1972 | Prague, Czechoslovakia | 1–0 | 2–1 | ||

| 15 | 1 November 1972 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 4–0 | 9–0 | 1974 FIFA World Cup qualification | |

| 16 | 8–0 | |||||

| 17 | 2 May 1973 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 3–2 | 3–2 | Friendly | |

| 18 | 22 August 1973 | Amsterdam, Netherlands | 2–0 | 5–0 | 1974 FIFA World Cup qualification | |

| 19 | 5–0 | |||||

| 20 | 29 August 1973 | Deventer, Netherlands | 2–0 | 8–1 | ||

| 21 | 4–0 | |||||

| 22 | 12 September 1973 | Oslo, Norway | 1–0 | 2–1 | ||

| 23 | 26 June 1974 | Gelsenkirchen, West Germany | 1–0 | 4–0 | 1974 FIFA World Cup | |

| 24 | 4–0 | |||||

| 25 | 3 July 1974 | Dortmund, Germany | 2–0 | 2–0 | ||

| 26 | 4 September 1974 | Stockholm, Sweden | 1–0 | 5–1 | Friendly | |

| 27 | 25 September 1974 | Helsinki, Finland | 1–1 | 3–1 | UEFA Euro 1976 qualifying | |

| 28 | 2–1 | |||||

| 29 | 20 November 1974 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 2–1 | 3–1 | ||

| 30 | 3–1 | |||||

| 31 | 22 May 1976 | Brussels, Belgium | 2–1 | 2–1 | ||

| 32 | 13 October 1976 | Rotterdam, Netherlands | 2–1 | 2–2 | 1978 FIFA World Cup qualification | |

| 33 | 26 March 1977 | Antwerp, Belgium | 2–0 | 2–0 |

Managerial statistics

| Team | From | To | Record | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | W | D | L | Win % | |||