Starčevo culture

| |

| Horizon | First Temperate Neolithic, Old Europe |

|---|---|

| Period | Neolithic Europe |

| Dates | circa 6,200 B.C.E. — circa 4,500 B.C.E. |

| Type site | Starčevo site |

| Preceded by | Iron Gates culture, Lepenski Vir culture, Sesklo culture, Neolithic Greece |

| Followed by | Karanovo culture, Vinča culture, Tisza culture, Hamangia culture, Gumelnița culture, Kakanj culture, Sopot culture, Linear Pottery culture |

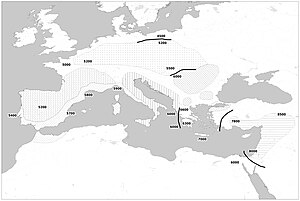

The Starčevo culture is an archaeological culture of Southeastern Europe, dating to the Neolithic period between c. 6200 and 4500 BCE.[1][2] It originates in the spread of the Neolithic package of peoples and technological innovations including farming and ceramics from Anatolia to the area of Sesklo. The Starčevo culture marks its spread to the inland Balkan peninsula as the Cardial ware culture did along the Adriatic coastline. It forms part of the wider Starčevo–Körös–Criş culture which gave rise to the central European Linear Pottery culture c. 700 years after the initial spread of Neolithic farmers towards the northern Balkans.[3]

The Starčevo site, the type site, is located on the north bank of the Danube near the village of Starčevo in Serbia (Vojvodina province), opposite Belgrade.

Origins

[edit]

The Starčevo culture represents a northern expansion of Early Neolithic Farmers who settled from Anatolia to present-day central Greece and expanded northwards. It forms part of the wider Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture. The river routes which traverse present-day North Macedonia have been suggested as the potential path of the movement of peoples and farming knowledge.[4] The Sesklo site has been generally viewed as the direct point of northwards expansion, but in 2020 radiocarbon dating across several sites showed that the site in Mavropigi (ca. 180 northwest of Sesklo) is a much more probable point of origin of the population movement along the river routes towards the central Balkans.[5] As of 2020, the two oldest dated sites are Crkvina near Miokovci, Serbia and Runik, Kosovo which are statistically indistinguishable to each other and have been dated to ca. 6238 BCE (6362-6098 BCE at 95% CI) and ca. 6185 BCE (6325–6088 BCE at 95% Cl) respectively.[6]

These two earliest sites were followed by a second cluster of sites that developed ca. 6200-6000 BCE in southern and central Serbia. The next expansion is located in eastern Serbia (Lepenski Vir) ca. 6100 BCE and since ca. 6000 BCE another cluster of settlements appears in northern Serbia. This general route of expansion suggests a wave of expansion model along river routes like the Morava Valley, but it is not a strictly defined model as not all northern sites are of a later date in comparison to sites to the south of them and vice versa.[6]

Archaeogenetics

[edit]In a 2017 genetic study published in Nature, the remains of five males ascribed to the early Starčevo culture from Hungary were analyzed. With regards to Y-DNA extracted, three belonged to subclades of G2a2, and two belonged to H2. mtDNA extracted were subclades of T1a2, K1a4a1, N1a1a1, W5 and X2d1.[7][8] A 2018 study published in Nature analyzed three samples from Croatia and one from Serbia, they belonged to Y-DNA haplogroup C-CTS3151, H2-L281 and I2 while mtDNA haplogroup J1c2, K1a4a1, U5b2b and U8b1b1.[9][10] In 2022 were analysed two samples, female from Grad-Starčevo with mtDNA haplogroup T2e2 and male from Vinča-Belo Brdo with Y-DNA haplogroup G2a2a1a3 and mtDNA haplogroup HV-16311.[11] According to ADMIXTURE analysis, Starčevo samples had approximately 87-100% Early European Farmers, 0-9% Western Hunter-Gatherer and 0-10% Western Steppe Herders-related ancestry.[10] A 2024 study published in Nature Human Behaviour tested 17 samples from Serbia, Croatia, Romania and Hungary, found Y-DNA haplogroups were G2a2b, G2a2b2a1a1c, G2a2a1a, G2a2a1a2a2a1, C1a2 (x2), R1b, H and F, while mtDNA haplogroups were H (x2), HV0a, J1c, J1b1, J2b1, J2b1d, K1a2, K1a4, K1a5, K1b1, K2, N1a1a, T2b (x2) and T2e.[12]

Characteristics and related cultures

[edit]

The pottery is usually coarse but finer fluted and painted vessels later emerged. A type of bone spatula, perhaps for scooping flour, is a distinctive artifact. The Körös is a similar culture in Hungary named after the River Körös with a closely related culture which also used footed vessels but fewer painted ones. Both have given their names to the wider culture of the region in that period.

Parallel and closely related cultures also include the Karanovo culture in Bulgaria, Criş in Romania and the pre-Sesklo in Greece.

Sites

[edit]

The Starčevo culture covered a sizable area that included much of present-day western and southern Serbia, Montenegro (except for the coastal region), Kosovo, parts of eastern Albania, eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina, western Bulgaria, eastern Croatia, Hungary, North Macedonia and Romania.[1][13]

The westernmost locality of this culture can be found in Croatia, in the vicinity of Ždralovi, a part of the town of Bjelovar. The region of Slavonia in present-day Croatia is the westernmost area of settlement of the Starčevo culture. Between 6200-5500 BCE, this area saw intensive habitation and land use organized around Zadubravlje, Galovo, Sarvaš, Pepelane, Stari Perkovci and other sites.[14] This was the final stage of the culture. Findings from Ždralovi belong to a regional subtype of the final variant in the long process of development of that Neolithic culture.

In 1990, Starčevo was added to the Archaeological Sites of Exceptional Importance list, protected by Republic of Serbia.

In Kosovo, the Starčevo material culture has been found in pre-Vinca layers in the sites of Vlashnjë and Runik.

Gallery

[edit]-

Sculpture from Tumba Madžari, North Macedonia

-

"Red-haired goddess" figurine

-

Altar table from Tumba Madžari

See also

[edit]- Körös culture

- Criş culture

- Archaeological Sites of Exceptional Importance

- Prehistoric Serbia

- Vinča culture

References

[edit]- ^ a b Istorijski atlas, Intersistem Kartografija, Beograd, 2010, page 11.

- ^ Chapman 2000, p. 237.

- ^ Hofmanová 2017, p. 18.

- ^ Gyulai 2016, p. 125.

- ^ Porčić et al. 2020, p. 3.

- ^ a b Porčić et al. 2020, p. 6

- ^ Lipson 2017.

- ^ Narasimhan 2019.

- ^ Mathieson 2018.

- ^ a b Patterson, Isakov & Booth 2022.

- ^ Marchi 2022.

- ^ Gelabert, Bickle & Hofmann 2024.

- ^ Becker 2006.

- ^ Rajković & Vitezović 2020, p. 156.

Sources

[edit]- Books

- Chapman, John (2000). Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places, and Broken Objects. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-15803-9.

- Gyulai, Ference (2016). "Seed and fruit remains associated with neolithic origins in the Carpathia Basin". In Colledge, Sue; Connolly, James (eds.). The Origins and Spread of Domestic Plants in Southwest Asia and Europe. Routledge. ISBN 978-1315417608.

- Trbuhović, V. (2006). Indoevropljani [Indo-Europeans]. Belgrade: Pešić i sinovi.

- Trifunović, Lazar, ed. (1968). Неолит Централног Балкана [Les regions centrales des Balkans a l'epoque neolithique]. Belgrade: Narodni muzej Beograd.

- Stalio, B.; Vukmanović, M. (1977). Neolit na tlu Srbije. Narodni muzej.

- Nenad N. Tasić (2009). Neolitska kvadratura kruga. Zavod za Udžbenike. ISBN 978-86-17-16535-0.

- Mallory, James P. (2006) [1991]. Indoeuropljani: zagonetka njihova podrijetla: jezik, arheologija, mit [In Search of the Indo-Europeans: Language, Archaeology and Myth] (Translated ed.). Školska knjiga. ISBN 978-953-0-61568-7.

- Journals

- Gelabert, Pere; et al. (29 November 2024). "Social and genetic diversity in first farmers of central Europe". Nature Human Behaviour. doi:10.1038/s41562-024-02034-z.

- Hofmanová, Zuzana (2017). Palaeogenomic and Biostatistical Analysis of Ancient DNA Data from Mesolithic and Neolithic Skeletal Remains (PDF) (PhD). Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz.

- Lipson, Mark (November 16, 2017). "Parallel palaeogenomic transects reveal complex genetic history of early European farmers". Nature. 551 (7680). Nature Research: 368–372. Bibcode:2017Natur.551..368L. doi:10.1038/nature24476. PMC 5973800. PMID 29144465.

- Marchi, Nina (12 May 2022). "The genomic origins of the world's first farmers". Cell. 185 (11). Cell Press: 1842–1859. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2022.04.008. hdl:20.500.11850/563063. PMC 9166250. PMID 35561686.

- Mathieson, Iain (February 21, 2018). "The Genomic History of Southeastern Europe". Nature. 555 (7695). Nature Research: 197–203. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..197M. doi:10.1038/nature25778. PMC 6091220. PMID 29466330.

- Mikić, Živko (1989). "Прилог антрополошком упознавању неолита у Србији". Гласник Српског археолошког друштва. 5. Belgrade: 18–26.

- Narasimhan, Vagheesh M. (September 6, 2019). "The formation of human populations in South and Central Asia". Science. 365 (6457). American Association for the Advancement of Science. eaat7487. bioRxiv 10.1101/292581. doi:10.1126/science.aat7487. PMC 6822619. PMID 31488661.

- Patterson, Nick; et al. (2022). "Large-scale migration into Britain during the Middle to Late Bronze Age". Nature. 601 (7894): 588–594. Bibcode:2022Natur.601..588P. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04287-4. PMC 8889665. PMID 34937049. S2CID 245509501.

- Porčić, Marko; Blagojević, Tamara; Pendić, Jugoslav; Stefanović, Sofija (2020). "The timing and tempo of the Neolithic expansion across the Central Balkans in the light of the new radiocarbon evidence". Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports. 33: 102528. Bibcode:2020JArSR..33j2528P. doi:10.1016/j.jasrep.2020.102528.

- Rajković, Dragana; Vitezović, Selena (2020). "The Starčevo Culture Horizon at the Site of Kneževi Vinogradi (Eastern Croatia). Lithic and Osseous Industries". Documenta Praehistorica. XLVII. doi:10.4312/dp.47.9.

- Тасић, Н., 1998. Старчевачка култура. Во Тасиђ Н.(уред.) Археолошко благо Косова и Метохије, Од неолита до раног средљег века. Музеј у Приштини. Београд: Српска Академија Наука и Уметности, pp. 30–55.

- Manson, J.L., 1992. A reanalysis of Starcevo culture ceramics: Implications for neolithic development in the Balkans.

- Kalicz, N., Virág, Z.M. and Biró, K.T., 1998. The northern periphery of the Early Neolithic Starčevo culture in south-western Hungary: a case study of excavation at Lake Balaton.

- Minichreiter, K., 2001. The architecture of Early and Middle Neolithic settlements of the Starčevo culture in Northern Croatia. Documenta Praehistorica, 28, pp. 199–214.

- Clason, A.T., 2016. Padina and Starčevo: game, fish, and cattle. Palaeohistoria, 22, pp. 141–173.

- Bartosiewicz, L., 2005. Plain talk: animals, environment, and culture in the Neolithic of the Carpathian Basin and adjacent areas. Un) settling the Neolithic. Oxbow, Oxford, pp. 51–63.

- Barker, G., 1975, December. Early Neolithic land use in Yugoslavia. In Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society (Vol. 41, pp. 85–104). Cambridge University Press.

- Regenye, J., 2007. A Starcevo-kultúra települése a Tihanyi-félszigeten (A settlement of the Starcevo culture on the Tihany peninsula). Osrégészeti Levelek. Prehistoric Newsletter, pp. 8–9.

- Tasic, N., 2000. Salt was used in the Early and Middle Neolithic of the Balkan Peninsula. BAR International Series, 854, pp. 35–40.

- Bogucki, P., 1996. The spread of early farming in Europe. American Scientist, 84(3), pp. 242–253.

- Bánffy, E., 2004. Advances in the research of the Neolithic transition in the Carpathian Basin. LBK dialogues: studies in the formation of the Linear Pottery Culture. British Archaeological Reports. Oxford: Archaeopress. p, pp. 49–70.

- Leković, V., 1990. The vinčanization of Starčevo culture. In Vinča and its world, International symposium–The Danubian region from (Vol. 6000, pp. 67–74).

- Boric, D., 1996. Social dimensions of mortuary practices in the Neolithic: a case study. Starinar, (47), pp. 67–83.

- Vitezović, S., 2012. The white beauty-Starčevo culture jewellery. Documenta Praehistorica, 39, p. 215.

- Regenye, J.U.D.I.T., 2010. What about the other side: Starčevo and LBK settlements north of Lake Balaton. Neolithization of the Carpathian basin: northernmost distribution of the Starčevo/Körös culture (Kraków/Budapest 2010), pp. 53–64.

- Brukner, B., 2006. A Contribution to the Study of Establishment of Ethnic and Cultural (Dis) continuity at the Transition from the Starčevo to the Vinča culture group. From Starčevo to Vinča culture, Current problems of the Transition Period, Proceedings from the International round table, Zrenjanin 1996, pp. 165–178.

- Vitezović, S., 2014. Antlers as raw material in the Starčevo culture. Archaeotechnology: Studying Technology from Prehistory to the Middle Ages, Srpsko arheološko društvo, Beograd, pp. 151–176.

- Nikolić, D., 2005. The development of pottery in the Middle Neolithic and chronological systems of the Starčevo culture. Glasnik Srpskog arheološkog društva, 21, pp. 45–70.

- Marinković, S., 2006. Starčevo Culture in Banat. Current Problems of the Transition Period from the Starčevo to the Vinča Culture. National Museum Zrenjanin, 1, pp. 63–79.

- Minichreiter, K., 2010. Above-ground Structures in the Settlements of the Starčevo Culture. Prilozi Instituta za arheologiju u Zagrebu, 26(1).

- Websites

- Becker, Valeska (2006) [Translated 2008]. "The Starčevo culture". Donau-Archäologie. Archived from the original on 2018-03-02. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

Further reading

[edit]- Shennan, Stephen (2018). The First Farmers of Europe: An Evolutionary Perspective. Cambridge World Archaeology. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781108386029. ISBN 9781108422925.

External links

[edit]- Archaeological cultures of Europe

- Neolithic cultures of Europe

- Archaeological cultures in Albania

- Archaeological cultures in Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Archaeological cultures in Croatia

- Archaeological cultures in Hungary

- Archaeological cultures in Kosovo

- Archaeological cultures in North Macedonia

- Archaeological cultures in Montenegro

- Archaeological cultures in Romania

- Archaeological cultures in Serbia

- Prehistory of Southeastern Europe

- Stone Age Europe

- Neolithic Serbia

- Prehistoric Hungary

- Prehistoric Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Prehistoric Serbia

- Prehistory of Vojvodina

- History of Banat

- Ancient peoples

- 7th millennium BC

- 6th millennium BC

- 5th millennium BC

- Starčevo–Körös–Criș culture