Joseph Beuys

Joseph Beuys | |

|---|---|

Offset poster for Beuys' 1974 US lecture-series "Energy Plan for the Western Man", Ronald Feldman Gallery | |

| Born | Joseph Heinrich Beuys 12 May 1921 |

| Died | 23 January 1986 (aged 64) |

| Education | Kunstakademie Düsseldorf |

| Known for | Performance, sculpture, visual art, sociophilosophy, theory of art |

| Notable work | How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (1965) Fettecke (1965) |

| Spouse |

Eva Wurmbach

(m. 1959) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

Joseph Heinrich Beuys (/bɔɪs/ BOYSS, German: [ˈjoːzɛf ˈbɔʏs]; 12 May 1921 – 23 January 1986) was a German artist, teacher, performance artist, and art theorist whose work reflected concepts of humanism, sociology. With Heinrich Böll, Johannes Stüttgen, Caroline Tisdall, Robert McDowell, and Enrico Wolleb, Beuys created the Free International University for Creativity & Interdisciplinary Research (FIU). Through his talks and performances, he also formed The Party for Animals and The Organisation for Direct Democracy. He was a member of a Dadaist art movement Fluxus and singularly inspirational in developing of Performance Art, called Kunst Aktionen, alongside Wiener Aktionismus that Allan Kaprow and Carolee Schneemann termed Art Happenings. Today, internationally, the largest performance art group is BBeyond in Belfast, led by Alastair MacLennan who knew Beuys and like many adapts Beuys's ethos.

Beuys is known for his "extended definition of art" in which the ideas of social sculpture could potentially reshape society and politics. He frequently held open public debates on a wide range of subjects, including political, environmental, social, and long-term cultural issues.[1][2]

Beuys' social sculpture proposals and underpinning ideas have been extensively explored, shared and developed through the practices, pedagogies, actions and writings of his master student and collaborator Shelley Sacks, first in South Africa in the 1970s as a branch of the Free International University (FIU); in the first Social Sculpture Colloquium, hosted by the Goethe Institute in Glasgow (1995); from 1997-2018 as Professor in Social Sculpture in the Social Sculpture Research Unit (SSRU) at Oxford Brookes University, where Johannes Stüttgen, Caroline Tisdall and Volker Harlan were research fellows; and since 2021, through the Social Sculpture Lab, curated by Sacks and hosted by the Documenta Archive in 2021 for the Beuys Centenery. The Social Sculpture Lab continues to engage with, develop and share Beuys' social sculpture understandings through such initiatives as the 7000 HUMANS Global Social Forest,. which has close connections with Beuys' 7000 Oaks, Sacks' social sculpture-connective practice methodologies, and a growing network of Social Sculpture Hubs in Germany, India, Holland, Brazil and UK.

Beuys was professor at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf from 1961 until 1972. He was a founding member and life-long supporter of the German Green Party.

Biography

[edit]Childhood and early life in the Third Reich (1921–1941)

[edit]Joseph Beuys was born in Krefeld, Germany, on 12 May 1921, to Josef Jakob Beuys (1888–1958), a merchant, and Johanna Maria Margarete Beuys née Hülsermann (1889–1974). Soon after his birth, the family moved from Krefeld to Kleve, an industrial town in Germany's Lower Rhine region, close to the Dutch border. Beuys attended primary school at the Katholische Volksschule and secondary school at the Staatliches Gymnasium Cleve (now the Freiherr-vom-Stein-Gymnasium). While in school he developed skills in drawing and took lessons in piano and cello. Other interests included the natural sciences, as well as Nordic history and mythology. By his own account, when the Nazi Party staged their book-burning in Kleve on 19 May 1933 in his school courtyard, he salvaged the book Systema Naturae by Carl Linnaeus "... from that large, flaming pile".[3]

In 1936, Beuys was a member of the Hitler Youth; the organization at that time included a large majority of German children and adolescents, and later that year membership became compulsory. He participated in the Nuremberg rally in September 1936. He was 15 years old at the time.[4]

Given his early interest in natural sciences, Beuys had considered a career in medical studies, but in his last years of school he became interested in pursuing a career in sculpture, possibly influenced by pictures of Wilhelm Lehmbruck's sculptures.[5] In around 1939 he began working part-time at a circus, where his responsibilities included posturing and taking care of animals. He held the job for about a year.[6] He graduated from school in the spring of 1941, having successfully earned his Abitur.

World War II (1941–1945)

[edit]Although he finally opted for a career in medicine,[7] in 1941, Beuys volunteered for the Luftwaffe,[8] and began training as an aircraft radio operator under the tutelage of Heinz Sielmann in Posen, Poland (now Poznań). They both attended lectures on biology and zoology at the University of Posen, at that time a Germanized university. During this time he began to consider pursuing a career as an artist.[9]

In 1942, Beuys was stationed in the Crimea and was a member of various combat bomber units. From 1943 onward, he was deployed as rear-gunner in a Ju 87 "Stuka" dive-bomber, initially stationed in Königgrätz, later moving to the eastern Adriatic region. Drawings and sketches from this time have been preserved, and his characteristic style is evident in this early work.[3] On 16 March 1944, Beuys's plane crashed on the Crimean Front close to Znamianka, then Freiberg Krasnohvardiiske Raion.[10] Drawing from this incident, Beuys fashioned the myth that he was rescued from the crash by nomadic Tatar tribesmen, who wrapped his broken body in animal fat and felt and nursed him back to health:

"Had it not been for the Tartars I would not be alive today. They were the nomads of the Crimea, in what was then no man's land between the Russian and German fronts, and favoured neither side. I had already struck up a good relationship with them and often wandered off to sit with them. 'Du nix njemcky' they would say, 'du Tartar,' and try to persuade me to join their clan. Their nomadic ways attracted me of course, although by that time their movements had been restricted. Yet, it was they who discovered me in the snow after the crash, when the German search parties had given up. I was still unconscious then and only came round completely after twelve days or so, and by then I was back in a German field hospital. So the memories I have of that time are images that penetrated my consciousness. The last thing I remember was that it was too late to jump, too late for the parachutes to open. That must have been a couple of seconds before hitting the ground. Luckily I was not strapped in – I always preferred free movement to safety belts ... My friend was strapped in and he was atomized on impact – there was almost nothing to be found of him afterwards. But I must have shot through the windscreen as it flew back at the same speed as the plane hit the ground and that saved me, though I had bad skull and jaw injuries. Then the tail flipped over and I was completely buried in the snow. That's how the Tartars found me days later. I remember voices saying 'Voda' (Water), then the felt of their tents, and the dense pungent smell of cheese, fat, and milk. They covered my body in fat to help it regenerate warmth, and wrapped it in felt as an insulator to keep warmth in."[11]

Records state that Beuys remained conscious, was recovered by a German search commando, and that there were no Tatars in the village at the time. Beuys was brought to a military hospital where he stayed for three weeks, from 17 March to 7 April.[12] It is consistent with Beuys' work that his biography would have been subject to his own reinterpretation;[13] this particular story has served as a powerful origin myth for Beuys's artistic identity, and has provided an initial interpretive key to his use of unconventional materials, amongst which felt and fat were central.[14]

Despite prior injuries, he was deployed to the Western Front in August 1944, assigned to a poorly-equipped and trained paratrooper unit.[3] He received a gold Wound Badge for having been wounded in action over five times. On the day after the German unconditional surrender (8 May 1945), Beuys was taken prisoner in Cuxhaven and brought to a British internment camp from which he was released three months later, on 5 August. He returned to his parents who had moved to a suburb of Kleve.

Studies and beginnings (1945–1960)

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2017) |

After returning to Kleve, Beuys met local sculptor Walter Brüx and painter Hanns Lamers, who encouraged him to take up art as a full-time career. He joined the Kleve Artists Association, which had been established by Brüx and Lamers. On 1 April 1946, Beuys enrolled in the monumental sculpture program at the Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts. Initially he was assigned to the class of Joseph Enseling, who had a more traditional, representational focus,[3] but he managed to change his mentor after three semesters, joining the small class of Ewald Mataré in 1947, who had rejoined the academy the previous year, after having been banned by the Nazis in 1939. The anthroposophical philosophy of Rudolf Steiner became an increasingly important basis for Beuys's philosophy. In his view it is "...an approach that refers to reality in a direct and practical way, and that by comparison, all forms of epistemological discourse remain without direct relevance to current trends and movements."[3] Reaffirming his interest in science, Beuys re-established contact with Heinz Sielmann, and assisted with a number of nature- and wildlife documentaries in the region between 1947 and 1949.

In 1947 Beuys, along with other artists (including Hann Trier), founded the group 'Donnerstag-Gesellschaft' (Thursday Group).[15] The group organised discussions, exhibitions, events and concerts between 1947 and 1950 in Alfter Castle.

In 1951, Mataré accepted Beuys into his master class[a] where he shared a studio with Erwin Heerich,[16] that he kept until 1954, a year after graduation. Nobel laureate Günter Grass recollects Beuys's influence in Mataré's class as shaping "a Christian anthroposophic atmosphere".[17] He read Joyce, impressed by the "Irish-mythological elements" in his works,[3] the German romantics Novalis and Friedrich Schiller, and studied Galileo and Leonardo, whom he admired as examples of artists and scientists who are conscious of their position in society and who work accordingly.[3] Early shows include participation in the Kleve Artists Association annual exhibition in Kleve's Villa Koekkoek, where Beuys showed aquarelles and sketches, a solo show at the home of Hans and Franz Joseph van der Grinten in Kranenburg as well as a show in the Von der Heydt Museum in Wuppertal.

Beuys finished his education in 1953, graduating at age 32 as master student from Mataré's class. He had a modest income from a number of craft-oriented commissions: a gravestone and several pieces of furniture. Throughout the 1950s, Beuys struggled both financially and from the trauma of his wartime experiences. His output consisted of drawings and sculptural work. Beuys explored a range of unconventional materials and developed his artistic agenda, exploring metaphorical and symbolic connections between natural phenomena and philosophical systems. Often difficult to interpret in themselves, his drawings constitute a speculative, contingent and hermetic exploration of the material world, myth and philosophy. In 1974, 327 drawings, the majority of which were made during the late 1940s and 1950s, were collected into a group entitled The Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland (a reference to Joyce), and exhibited in Oxford, Edinburgh, Dublin, and Belfast.

In 1956, artistic self-doubt and material impoverishment led to a physical and psychological crisis, and Beuys entered a period of serious depression. He recovered at the house of his most important early patrons, the van der Grinten brothers, in Kranenburg. In 1958, Beuys participated in an international competition for an Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial. His proposal did not win and his design was never realised. In 1958, Beuys began a cycle of drawings related to Joyce's Ulysses. Completed in around 1961, the six exercise books of drawings would constitute, Beuys declared, an extension of Joyce's seminal novel. In 1959, Beuys married Eva Wurmbach. They had two children, Wenzel (born 1961) and Jessyka (born 1964).

Academia and public (1960–1975)

[edit]In 1961, Beuys was appointed professor of monumental sculpture at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. His students were artists Anatol Herzfeld, Katharina Sieverding, Jörg Immendorff, Blinky Palermo, Peter Angermann, Walter Dahn, Johannes Stüttgen, Sigmar Polke and Friederike Weske. His youngest student was Elias Maria Reti who began to study art in his class at the age of 15.[18]

Beuys entered wider public consciousness in 1964, when he participated in a festival at the Technical College Aachen which coincided with the 20th anniversary of an assassination attempt on Adolf Hitler. Beuys created a performance or action (Aktion) which was interrupted by a group of students, one of whom attacked Beuys, punching him in the face. A photograph of the artist, nose bloodied and arm raised, was circulated in the media. It was for this 1964 festival that Beuys produced an idiosyncratic CV, which he titled Lebenslauf/Werklauf (Life Course/Work Course). The document was a self-consciously fictionalised account of the artist's life, in which historical events mingle with metaphorical and mythical speech (he refers to his birth as the 'Exhibition of a wound;' he claims his Ulysses Extension to have been carried out 'at James Joyce's request' – impossible, given that the writer was long dead by 1961). This document marks a blurring of fact and fiction that was to be characteristic of Beuys' self-created persona.

Beuys manifested his social philosophical ideas in abolishing entry requirements to his Düsseldorf class. Throughout the late 1960s, this renegade policy caused great institutional friction, coming to a head in October 1972 when Beuys was dismissed from his post. That year, he found 142 applicants who had not been accepted whom he wished to enroll under his teaching. Beuys and 16 students subsequently occupied the offices of the academy to force a hearing regarding their admission. They were admitted by the school, but the relationship between Beuys and the school was irreconcilable.[19] He again occupied the university offices with a group of students; the police were called and he was escorted laughing from the building. This was depicted in a photograph which was used to create a 1973 silkscreen print with the title Democracy Is Funny.[20] Shortly after, he was dismissed from his post. The dismissal, which Beuys refused to accept, produced a wave of protests from students, artists and critics. Although now without an institutional position, Beuys continued an intense schedule of public lectures and discussions, and became increasingly active in German politics. Despite this dismissal, the walkway on the academy's side of the Rhine is named for Beuys. Later in life, Beuys became a visiting professor at various institutions (1980–1985).

Teaching philosophy

[edit]"The most important discussion is epistemological in character," stated Beuys, demonstrating his desire for continuous intellectual exchange. Beuys attempted to apply philosophical concepts to his pedagogical practice. Beuys's action, How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare, exemplifies a performance that is especially relevant to the pedagogical field because it addresses "the difficulty of explaining things".[21] The artist spent three hours explaining his art to a dead hare with his head covered with honey and gold leaf, and Ulmer argues not only that the honey on the head but the hare itself are models of thinking, of man embodying his ideas in forms. Contemporary movements such as performance art may be considered 'laboratories' for a new pedagogy since "research and experiment have replaced form as the guiding force".[21]

During an Artforum interview with Willoughby Sharp in 1969, Beuys added to his famous statement – "teaching is my greatest work of art" – that "the rest is the waste product, a demonstration. If you want to express yourself you must present something tangible. But after a while this has only the function of a historic document. Objects aren't very important any more. I want to get to the origin of matter, to the thought behind it."[22] Beuys saw his role of an artist as a teacher or shaman who could guide society in a new direction.[23]

At the Düsseldorf Academy of Art, Beuys did not impose his artistic style or techniques on his students; in fact, he kept much of his work and exhibitions hidden from the classroom because he wanted his students to explore their own interests, ideas, and talents.[24] Beuys's actions were somewhat contradictory: while he was extremely strict about certain aspects of classroom management and instruction, such as punctuality and the need for students to take draftsmanship classes, he encouraged his students to freely set their own artistic goals without having to conform to set curricula.[24] Another aspect of Beuys's pedagogy was open "ring discussions" or Ringgesprache, where Beuys and his students discussed political and philosophical issues of the day, including the role of art, democracy, and the university in society. Some of his ideas espoused in class discussion and in his art-making included free art education for all, the discovery of creativity in everyday life, and the belief that "everyone [was] an artist."[25] Beuys himself encouraged peripheral activity and all manner of expression to emerge during the course of these discussions.[24] While some of Beuys's students enjoyed the open discourse of the Ringgesprache, others, including Palermo and Immendorf, disapproved of the classroom disorder and anarchic characteristics, eventually rejecting his methods and philosophies altogether.[24]

Beuys also advocated taking art outside of the boundaries of the (art) system and opening it up to multiple possibilities, bringing creativity into all areas of life. His nontraditional and anti-establishment pedagogical practice and philosophy made him the focus of much controversy, and to battle the policy of "restricted entry", under which only a few select students were allowed to attend art classes, he deliberately allowed students to over-enroll in his courses (Anastasia Shartin),[26] true to his belief those who have something to teach and those who have something to learn should come together.

The artist as shaman

[edit]According to Cornelia Lauf (1992),[full citation needed] "in order to implement his idea, as well as a host of supporting notions encompassing cultural and political concepts, Beuys crafted a charismatic artistic persona that infused his work with mystical overtones and led him to be called "shaman" and "messianic" in the popular press."

Beuys had adopted shamanism not only as a presentation mode of his art but also in his own life. Although the artist as a shaman has been a trend in modern art (Picasso, Gauguin), Beuys is unusual in that respect as he integrated "his art and his life into the shaman role."[27] Beuys believed that humanity, with its turn on rationality, was trying to eliminate emotions and thus eliminate a major source of energy and creativity. In his first lecture tour in America he espoused that humanity was in an evolving state and that as "spiritual" beings we ought to draw on both our emotions and our thinking as they represent the total energy and creativity for every individual. Beuys described how we must seek out and energize our spirituality and link it to our thinking powers so that "our vision of the world must be extended to encompass all the invisible energies with which we have lost contact."[28][29]

Beuys saw his performance art as shamanistic and psychoanalytic to both educate and heal the general public.

"It was thus a strategic stage to use the shaman's character but, subsequently, I gave scientific lectures. Also, at times, on one hand, I was a kind of modern scientific analyst, on the other hand, in the actions, I had a synthetic existence as shaman. This strategy aimed at creating in people an agitation for instigating questions rather than for conveying a complete and perfect structure. It was a kind of psychoanalysis with all the problems of energy and culture."[30]

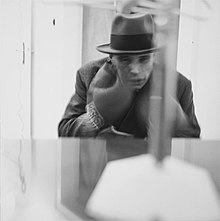

Beuys's art was considered both instructive and therapeutic – "His intention was to use these two forms of discourse and styles of knowledge as pedagogues." He used shamanistic and psychoanalytic techniques to "manipulate symbols" and affect his audience.[31] In his personal life, Beuys had adopted a felt hat, a felt suit, a cane and a vest as his standard look. The imagined story of him being rescued by Tartar herdsmen perhaps is an explanation for his adopting materials such as felt and fat.

Beuys experienced severe depression between 1955 and 1957. After recovering, he observed at the time that "his personal crisis"[This quote needs a citation] caused him to question everything in life, and he called the incident "a shamanistic initiation."[This quote needs a citation] He saw death not only in its inevitability for people, but also death in the environment, and through his art and his political activism, he became a strong critic of environmental destruction. He said at the time, "I don't use shamanism to refer to death, but vice versa – through shamanism, I refer to the fatal character of the times we live in. But at the same time I also point out that the fatal character of the present can be overcome in the future."[This quote needs a citation]

National and international recognition (1975–1986)

[edit]

The only major retrospective of Beuys work to be organised in Beuys's lifetime opened at the Guggenheim Museum in New York in 1979. The exhibition has been described as a "lightning rod for American criticism," eliciting as it did some powerful and polemical responses.[4]

Death

[edit]Beuys died of heart failure on 23 January 1986, in Düsseldorf.[32]

Body of work

[edit]Beuys's extensive body of work principally comprises four domains: works of art in a traditional sense (painting, drawing, sculpture and installations), performance, contributions to the theory of art and academic teaching, and social and political activities.

Artworks and performances

[edit]In 1962, Beuys befriended his Düsseldorf colleague Nam June Paik, a member of the Fluxus movement. This began what was to be a brief formal involvement with Fluxus, a loose international group of artists who championed radical erosion of artistic boundaries, bringing aspects of creative practice outside of the institution and into the everyday. Although Beuys participated in a number of Fluxus events, it soon became clear that he viewed the implications of art's economic and institutional framework differently. Indeed, whereas Fluxus was directly inspired by the radical Dada activities emerging during the First World War, Beuys in a 1964 broadcast (from the Second German Television Studio) a different message: Das Schweigen von Marcel Duchamp wird überbewertet ('The silence of Marcel Duchamp is overrated'). Beuys's relationship with the legacy of Duchamp and the readymade is a central (if often unacknowledged) aspect of the controversy surrounding his practice.

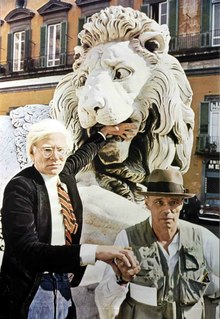

On 12 January 1985, Beuys, together with Andy Warhol and Kaii Higashiyama, became involved in the "Global-Art-Fusion" project. This was a fax art project, initiated by the conceptual artist Ueli Fuchser, in which faxes with drawings of all three artists were sent within 32 minutes around the world – from Düsseldorf (Germany) via New York (USA) to Tokyo (Japan), and received at Vienna's Palais-Liechtenstein Museum of Modern Art. This fax event was a sign of peace during the Cold War in the 1980s.[33]

How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare (performance, 1965)

[edit]

Beuys's first solo exhibition in a private gallery opened on 26 November 1965 with one of his most famous performances: How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. The artist could be viewed through the glass of the gallery's window. His face was covered in honey and gold leaf, and an iron slab was attached to his boot. In his arms he cradled a dead hare, into whose ear he uttered muffled noises as well as explanations of the drawings lining the walls. Such materials and actions had specific symbolic value for Beuys. For example, honey is the product of bees, and for Beuys (following Rudolf Steiner), bees represented an ideal society of warmth and brotherhood. Gold had its importance within alchemical enquiry, and iron, the metal of Mars, stood for a masculine principle of strength and connection to the earth. A photograph from the performance, in which Beuys sits with the hare, has been described "by some critics as a new Mona Lisa of the 20th century," though Beuys disagreed with the description.[34]

Beuys explained his performance this way:

"In putting honey on my head I am clearly doing something that has to do with thinking. Human ability is not to produce honey, but to think, to produce ideas. In this way the deathlike character of thinking becomes lifelike again. For honey is undoubtedly a living substance. Human thinking can be lively too. But it can also be intellectualized to a deadly degree, and remain dead, and express its deadliness in, say, the political or pedagogic fields. Gold and honey indicate a transformation of the head, and therefore, naturally and logically, the brain and our understanding of thought, consciousness and all the other levels necessary to explain pictures to a hare: the warm stool insulated with felt ... and the iron sole with the magnet. I had to walk on this sole when I carried the hare round from picture to picture, so along with the strange limp came the clank of iron on the hard stone floor—that was all that broke the silence, since my explanations were mute .... This seems to have been the action that most captured people's imaginations. On one level this must be because everyone consciously or unconsciously recognizes the problem of explaining things, particularly where art and creative work are concerned, or anything that involves a certain mystery or question. The idea of explaining to an animal conveys a sense of the secrecy of the world and of existence that appeals to the imagination. Then, as I said, even a dead animal preserves more powers of intuition than some human beings with their stubborn rationality. The problem lies in the word 'understanding' and its many levels, which cannot be restricted to rational analysis. Imagination, inspiration, and longing all lead people to sense that these other levels also play a part in understanding. This must be the root of reactions to this action, and is why my technique has been to try and seek out the energy points in the human power field, rather than demanding specific knowledge or reactions on the part of the public. I try to bring to light the complexity of creative areas."[34][failed verification]

Beuys produced many such spectacular, ritualistic performances, and he developed a compelling persona whereby he took on a liminal, shamanistic role, as if to enable passage between different physical and spiritual states. Further examples of such performances include: Eurasienstab (1967), Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony (1970), and I Like America and America Likes Me (1974).[19]

The Chief – Fluxus Chant (performance, installation, 1963–1964)

[edit]The Chief was first performed in Copenhagen in 1963 and in Berlin in 1964.[35] Beuys positioned himself on the gallery floor wrapped entirely in a large felt blanket, and remained there for nine hours. Emerging from either end of the blanket were two dead hares. Around him was an installation of copper rod, felt, fat, hair, and fingernails. Inside the blanket Beuys held a microphone into which he breathed, coughed, groaned, grumbled, whispered and whistled at irregular intervals, with the results amplified by a PA system as viewers observed from the doorway.[35]

In her book on Beuys, Caroline Tisdall wrote that The Chief "is the first performance in which the rich vocabulary of the next fifteen years is already suggested,"[35] and that its theme is "the exploration of levels of communication beyond human semantics, by appealing to atavistic and instinctual powers."[36] Beuys stated that his presence in the room "was like that of a carrier wave, attempting to switch off my own species' range of semantics."[37] He also said: "For me The Chief was above all an important sound piece. The most recurring sound was deep in the throat and hoarse like the cry of the stag....This is a primary sound, reaching far back. ... The sounds I make are taken consciously from animals. I see it as a way of coming into contact with other forms of existence beyond the human one. It's a way of going beyond our restricted understanding to expand the scale of producers of energy among co-operators in other species, all of whom have different abilities[.]"[37] Beuys also acknowledged the physical demands of the performance. "It takes a lot of discipline to avoid panicking in such a condition, floating empty and devoid of emotion and without specific feelings of claustrophobia or pain, for nine hours in the same position ... such an action ... changes me radically. In a way it's a death, a real action and not an interpretation."[37]

Writer Jan Verwoert noted that Beuys' "voice filled the room, while the source was nowhere to be found. The artist was the focus of attention, yet remained invisible, rolled up in a felt blanket throughout the duration of the event...visitors were...forced to stay in the neighboring room. They could see what was happening but remained barred from direct physical access to the event. The partial closing-off of the performance space from the audience space created distance, and at the same time increased the attraction of the artist's presence. He was present acoustically and physically as part of a piece of sculpture, but also absent, invisible, untouchable[.]"[38] Verwoert suggests that The Chief "can be read as a parable of cultural work in a public medium. The authority of those who dare — or are so bold as — to speak publicly results from the fact that they isolate themselves from the gaze of the public, under the gaze of the public, in order to still address it in indirect speech, relayed through a medium. What is constituted in this ceremony is authority in the sense of authorship, in the sense of a public voice....Beuys stages the creation of such a public voice as an event that is as dramatic as it is absurd. He thus asserts the emergence of such a voice as an event. At the same time, however, he also undermines this assertion through the lamentably powerless form by which this voice is produced: in emitting half-smothered inarticulate sounds that would have remained inaudible without electronic amplification."[38] Lana Shafer Meador wrote: "Inherent to The Chief were issues of communication and transformation .... For Beuys, his own muffled coughs, breaths, and grunts were his way of speaking for the hares, giving a voice to those who are misunderstood or do not possess their own....In the midst of this metaphysical communication and transmission, the audience was left out in the cold. Beuys deliberately distanced the viewers by physically positioning them in a separate gallery room — only able to hear, but not see what is occurring — and by performing the action for a grueling nine hours."[39]

Infiltration Homogen for Piano (performance, 1966)

[edit]Beuys performed Infiltration Homogen for Piano in Düsseldorf in 1966.[40] The result was a piano covered entirely in felt with two crosses made of red material affixed to its sides. Beuys wrote: "The sound of the piano is trapped inside the felt skin. In the normal sense a piano is an instrument used to produce sound. When not in use it is silent, but still has a sound potential. Here no sound is possible and the piano is condemned to silence."[40] He also said, "The relationship to the human position is marked by the two red crosses signifying emergency: the danger that threatens if we stay silent and fail to make the next evolutionary step...Such an object is intended as a stimulus for discussion, and in no way is to be taken as an aesthetic product."[40] During the performance he also used wax earplugs and drew and wrote on a blackboard.[41]

The piece is subtitled "The greatest composer here is the thalidomide child", and attempts to bring attention to the plight of children affected by the drug.[19][40] (Thalidomide was a sleep aid introduced in the 1950s in Germany. It was promoted to help relieve the symptoms of morning sickness and was prescribed in unlimited doses to pregnant women. However, it quickly became apparent that Thalidomide caused death and deformities in some children of mothers who had taken the drug. It was on the market for less than four years. In Germany around 2,500 children were affected.[19]) During his performance, Beuys held a discussion about the tragedy surrounding Thalidomide children.[19]

Beuys also prepared Infiltration Homogens for Cello, a cello wrapped in grey felt with a red cross attached,[42] for musician Charlotte Moorman, who performed it in conjunction with Nam June Paik.[41][43]

Caroline Tisdall noted how, in this work, "sound and silence, exterior and interior, are ... brought together in objects and actions as representatives of the physical and spiritual worlds."[40] Australian sculptor Ken Unsworth wrote that Infiltration "became a black hole: instead of sound escaping, sound was drawn into it ... It wasn't as if the piano was dead. I realised Beuys identified felt with saving and preserving life."[44] Artist Dan McLaughlin wrote of the "quiet absorptive silencing of an instrument capable of an infinity of expressions The power and potency of the instrument is dressed, swaddled even, in felt, legs and all, and creates a clumsy, pachyderm-like metaphor for a kind of silent entombment. But it is also a power incubated, protected and storing potential expressions ... pieces like Infiltration showcase the intuitive power Beuys had, understanding that some materials had invested in them human language and human gesture through use and proximity, through morphological sympathy."[45]

I Like America and America Likes Me (performance, 1974)

[edit]Art historian Uwe Schneede considers this performance pivotal for the reception of German avant-garde art in the United States since it paved the way for recognition of not only Beuys' own work but also that of contemporaries such as Georg Baselitz, Kiefer, Lüpertz, and many others in the 1980s.[46] In May 1974, Beuys flew to New York and was taken by ambulance to the site of the performance, a room in the René Block Gallery at 409 West Broadway.[47] Beuys lay on the ambulance stretcher swathed in felt. He shared this room with a coyote for eight hours over three days. At times he stood, wrapped in a thick, grey blanket of felt, leaning on a large shepherd's staff. At times he lay on the straw, at times he watched the coyote as the coyote watched him and cautiously circled the man or shredded the blanket to pieces, and at times he engaged in symbolic gestures, such as striking a large triangle or tossing his leather gloves to the animal; the performance continuously shifted between elements that were required by the realities of the situation and elements that had a purely symbolic character. At the end of the three days, Beuys hugged the coyote that had grown quite tolerant of him and was taken to the airport. Again he rode in a veiled ambulance, leaving America without having set foot on its ground. As Beuys later explained: 'I wanted to isolate myself, insulate myself, see nothing of America other than the coyote.'[46]

In 2013, Dale Eisinger of Complex ranked I Like America and America Likes Me the second greatest work of performance art ever, after Pandrogeny by Genesis P-Orridge.[48]

Celtic (Kinloch Rannoch) Scottish Symphony, Celtic+, Agnus Vitex Castus and Three Pots for The Poorhouse (performances 1970, 1971, 1972, 1973)

[edit]Richard Demarco invited Beuys to Scotland in May 1970 and again in August to show and perform in the Edinburgh International Festival with Günther Uecker, Blinky Palermo and other Düsseldorf artists plus Robert Filliou[49] where they took over the main spaces of the Edinburgh College of Art. The exhibition was a defining moment for British and European art, directly influencing several generations of artists and curators.

In Edinburgh in 1970, Beuys created ARENA for Demarco as a retrospective of his art up to that time, showed his installation The Pack (Beuys) and performed Celtic Kinloch Rannoch with Henning Christiansen and Johannes Stüttgen in support, seen by several thousands. This was Beuys' first use of blackboards and the beginning of nine trips to Scotland to work with Richard Demarco, and six to Ireland and five to England, working mainly with art critic Caroline Tisdall and Troubled Image Group artist Robert McDowell and others in the detailed formulation of the Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research (FIU) presented at documenta 6 in 1977, in London in 1978 and Edinburgh in 1980, as well as in many other iterations.

In Edinburgh, at the end of the 1970s the FIU became among four organisations that founded the German Green Party. Beuys became entranced by the periphery of Europe as a dynamic counter in cultural and economic terms to Europe's centralisation, and this included linking Europe's energies North-South to Italy and East-West in the Eurasia concept, with special emphasis on Celtic traditions in landscape, poetry, and myths that also define Eurasia. In his view anything that survives as art and ideas and beliefs, including the great religions for centuries or millennia, contain eternal truths and beauty. The truth of ideas and of 'thinking as form', the sculpture of energies across a wide and variegated spectrum from mythos and spirituality to materialism, Socialism and Capitalism, and of 'creativity = capital' encompassed for him the study of geology, botany, and animal life, finding meanings and precepts in all of these as much as in the study of society, philosophy and the human condition, and in his art practice as 'Social Sculpture'.

He adopted and developed a Gestalt way to examine and work with both organic and inorganic substances and human social elements, following Leonardo, Loyola, Goethe, Steiner, Joyce, and many other artists, scientists and thinkers, working with all visible and invisible aspects comprising a totality of cultural, moral and ethical significance as much as practical or scientific value. These trips inspired many works and performances. Beuys considered Edinburgh with its Enlightenment history as a laboratory of inspirational ideas. When visiting Loch Awe and Rannoch Moor on his May 1970 visit to Demarco he first conceived the necessity of the 7,000 Oaks work. After making the Loch Awe sculpture, at Rannoch Moor he began what became the Celtic (Kinlock Rannoch) Scottish Symphony performance, developed further in Basel the next year as Celtic+. The performance in Edinburgh included his first blackboard that later appeared in many performances when in discussion with the public. With it and his Eurasian staff he is a transmitter and, despite long periods of imperturbable stillness interspersed by Christiansen's 'sound sculptures', he also creates dialogue evoking artists' thoughts and in discussion with spectators. He collected gelatin representing crystalline stored energy of ideas that had been spread over the wall. In Basel the action including washing the feet of seven spectators. He immersed himself in water with reference to Christian traditions and baptism and symbolized revolutionary freedom from false preconceptions.

He then, as in Edinburgh, pushed a blackboard across the floor alternately writing or drawing on it for his audience. He put each piece in a tray and as the tray became full he held it above his head and convulsed, causing the gelatin to fall on him and the floor. He followed this with a quiet pause. He stared into emptiness for over half an hour, fairly still in both performances. During this time, he had a lance in his hand and was standing by the blackboard where he had drawn a grail. He took a protective stance. After this he repeated each action in the opposite order, ending with the washing with water as a final cleansing.[19] The performances were filled with Celtic symbolism with various interpretations or historic influences. This extended in 1972 with the performance Vitex Agnus Castus in Naples, of combining female and male elements and evoking much else, and extended further with I Like America and America Likes Me to have a performance dialogue with the original energy of America represented by the endangered yet highly intelligent coyote.

In 1974, in Edinburgh, Beuys worked with Buckminster Fuller in Demarco's 'Black & White Oil Conference', where Beuys talked of 'The Energy Plan of the Western Man' using blackboards in open discussion with audiences at Demarco's Forrest Hill Schoolhouse. In the 1974 Edinburgh Festival, Beuys performed Three Pots for the Poorhouse again using gelatin in Edinburgh's ancient poorhouse, continuing the development begun with Celtic Kinloch Rannoch. He met there Tadeusz Kantor directing Lovelies and Dowdies and was at Marina Abramović's first ever performance. In 1976, Beuys performed In Defence of the Innocent at the Demarco Gallery where he stood for the imprisoned gangster and sculptor Jimmy Boyle in a manner associating Boyle with the coyote. In 1980 Edinburgh Festival Beuys was at the FIU exhibition and performed Jimmy Boyle Days (the name of the blackboards he used in public discussions), and where he went on a hunger strike as a public protest and led with others in a legal action against the Scottish Justice system. This was the first case under the new European Human Rights Act. The eight performances should be understood as one continuum.

The concept of "Social Sculpture"

[edit]

During the 1960s Beuys formed his central theoretical concepts about arts' social, cultural and political function and potential.[50] Indebted to Romantic writers like Novalis and Schiller, Beuys was motivated by a belief in the power of universal human creativity and was confident about the potential for art to bring about revolutionary change. These ideas were founded in the body of social ideas of Rudolf Steiner, known as Social Threefolding, of which he was a vigorous and original proponent. This translated into Beuys's devising the concept of social sculpture, in which society as a whole was to be regarded as one great work of art (the Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk) to which each person can contribute creatively (perhaps Beuys's most famous phrase, borrowed from Novalis, is "Everyone is an artist"). In the video "Willoughby SHARP, Joseph Beuys, Public Dialogues (1974/120 min.)", a record of Beuys's first major public discussion in the U.S., Beuys elaborates three principles: Freedom, Democracy, and Socialism, saying that each of them depends on the other two in order to be meaningful. In 1973, Beuys wrote:

"Only on condition of a radical widening of definitions will it be possible for art and activities related to art [to] provide evidence that art is now the only evolutionary-revolutionary power. Only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system that continues to totter along the deathline: to dismantle in order to build 'A SOCIAL ORGANISM AS A WORK OF ART' ... EVERY HUMAN BEING IS AN ARTIST who – from his state of freedom – the position of freedom that he experiences at first-hand – learns to determine the other positions of the TOTAL ART WORK OF THE FUTURE SOCIAL ORDER."[51]

In 1982, he was invited to create a work for documenta 7. He delivered a large pile of basalt stones. From above one could see that the pile of stones was a large arrow pointing to a single oak tree that he had planted. He announced that the stones should not be moved unless an oak tree was planted in a stone's new location. 7,000 oak trees were then planted in Kassel, Germany.[52] This project exemplified the idea that a social sculpture was defined as interdisciplinary and participatory. Beuys wanted to effect environmental and social change through this project. The Dia Art Foundation is perpetuating his project and has planted more trees and paired them with basalt stones, too.

Beuys said that:

My point with these seven thousand trees was that each would be a monument, consisting of a living part, the live tree, changing all the time, and a crystalline mass maintaining its shape, size, and weight. This stone can be transformed only by taking from it, when a piece splinters off, say, never by growing. By placing these two objects side by side, the proportionality of the monument's two parts will never be the same.[53]

"Sonne Statt Reagan"

[edit]In 1982, Beuys recorded a music video for a song he had written entitled "Sonne statt Reagan"[54] which translates to "Sun, not Rain/Reagan", an anti-Reagan political piece that included some German puns and reinforced some key messages of Beuys's career (at least, after his days as a soldier) – namely, a liberal, pacifist political attitude, a desire to perpetuate open discourse about art and politics, a refusal to sanctify his own image and 'artistic reputation' by only doing the kinds of work other people expected he would do, and above all an openness to exploring different media forms to get across the messages he wanted to convey. His continued commitment to the demystification and dis-institutionalization of the 'art world' was never more clear than it is here.[original research?]

Beuys made it clear that he regarded this song as a work of art, not the "pop" product it appears to be, which is apparent from the moment one views it. This becomes clearer when one reads the lyrics, which are aimed directly at Reagan, the military complex and whoever is trying to defrost the "Cold War" to make it "Hot." The song is perhaps best understood in the context of intense liberal and progressive frustration in 1982. Beuys warns Reagan et al. that the peace-loving masses are behind him, including Americans as well.[55] Some discourse about Beuys by those who consider his body of artwork sacrosanct has avoided "Sonne statt Reagan", regarding the video as an outlier, even to be ridiculed. Yet by choosing the vehicle of popular music, Beuys showed commitment to his views and to engage a broad means to have them reach people.

7,000 Oaks

[edit]Among Beuys's more ambitious pieces of social sculpture was the 7,000 Oaks project, one of enormous scope which met with some controversy.

Political activities

[edit]Amongst other things, Beuys founded (or co-founded) the following political organisations: German Student Party (1967), Organization for Direct Democracy Through Referendum (1971), Free International University for Creativity and Interdisciplinary Research (1974), and German Green Party Die Grünen (1980). Beuys became a pacifist and a vocal opponent of nuclear weapons; he campaigned for environmental causes (in fact he was elected as a Green Party candidate for the European Parliament). Some of his art directly addressed the political issues of the day among groups with which he affiliated. His song and music video "Sun Instead of Reagan" (1982) expresses the theme of regeneration (optimism, growth, hope) running through his life and work as well as his interest in contemporary nuclear politics: "But we want: sun instead of Reagan, to live without weapons! Whether West, whether East, let missiles rust!"[56]

Critiques

[edit]The Guggenheim retrospective and catalogue offered a comprehensive view of Beuys's practice and rhetoric to an American critical audience. Although for some time he had been a central figure in the post-war European artistic consciousness, his work to that point had had only fleeting and partial exposure among American audiences. In 1980, building on scepticism voiced by Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers, who in a 1972 Open Letter had compared Beuys to Wagner,[57] art historian Benjamin Buchloh (who was teaching at Staatliche Kunstakademie, just like Beuys) launched a polemically forceful attack on Beuys.[58] The essay was a vitriolic and extensive critique of both Beuys's rhetoric (referred to as "simple-minded utopian drivel") and persona (Buchloh regards Beuys as both infantile and messianic).[59]

First, Buchloh notes Beuys' fictionalisation of his own biography,[60] which he sees as symptomatic of a dangerous cultural tendency to disavow past trauma and retreat into the realms of myth and esoteric symbolism. Buchloh critiques Beuys for failing to acknowledge and engage with Nazism, the Holocaust, and their implications. Buchloh then criticizes Beuys for displaying an inability or reluctance to engage with the consequences of the work of Marcel Duchamp, in particular, a failure to acknowledge the framing function of the art institution and the inevitable dependence upon such institutions to create meaning for art objects. If Beuys championed art's power to foster political transformation, Buchloh asserts that Beuys nevertheless failed to acknowledge the limits imposed upon such aspirations by the art museum and dealership networks which, he asserts, may serve somewhat less utopian ambitions. For Buchloh, rather than acknowledging the collective and contextual formation of meaning, Beuys instead tried to prescribe and control the meanings of his art, often through dubious esoteric or symbolic codings. Buchloh's critique has been expounded upon by commentators like Stefan Germer and Rosalind Krauss.[61][62]

Rehabilitation

[edit]Buchloh's critique has been subject to revision. His attention is given to dismantling a mythologized artistic persona and utopian rhetoric, which he regarded to be irresponsible. Since Buchloh's essay was published, however, much new archival material has come to light, most significantly Beuys' proposal for an Auschwitz-Birkenau memorial, submitted in 1958. Some argue that the existence of such a project invalidates Buchloh's claim that Beuys retreated from engaging with the Nazi legacy, a point that Buchloh himself has acknowledged, although the charges of romanticism and self-mythologizing remain.[63]

Beuys' charisma and eclecticism may have polarized some of his audience. His work has attracted admirers and devotees, some who may uncritically accept Beuys' own explanations as interpretive solutions to his work. In contrast, some of those in Buchloh's camp charge Beuys' with weak rhetoric and arguments and dismiss his work as bogus. Relatively few accounts have addressed works themselves, with the exception of scholarship from art historians like Gene Ray,[64] Claudia Mesch,[65][66][67] Christa-Maria Lerm Hayes,[68] Briony Fer,[69] Alex Potts,[70] and others. The drive here has been to separate Beuys' work from his rhetoric, and to explore both wider discursive formations within which Beuys operated (this time, productively), and the physical properties of the works themselves.

Examples of contemporary artists who have drawn from the legacy of Beuys include AA Bronson, former member of the artists' collaborative General Idea, who, not without irony, adopts the subject position of the shaman to reclaim art's restorative, healing powers; Andy Wear whose installations are deliberately formed according to the Beuysian notion of 'stations' and are (in particular, referencing the Block Beuys in Darmstadt) essentially a constellation of works performed or created external to the installation; and Peter Gallo, whose drawing cycle I wish I could draw like Joseph Beuys features stretches of Beuys' writings combined with images traced from vintage gay pornography onto random pieces of paper.

Additionally, the counter-institution of the FIU or Free International University, initiated by Beuys, continues as a publishing concern (FIU Verlag) and has active chapters in German cities including Hamburg, Munich, and Amorbach.

Exhibitions and collections

[edit]| External videos | |

|---|---|

| |

Franz Joseph and Hans van der Grinten organized Beuys's first solo show at their house in Kranenburg in 1953. The Alfred Schmela Galerie was the first commercial gallery to hold a Beuys solo exhibition in 1965. Beuys participated for the first time in documenta in Kassel in 1964. In 1969, he was included in Harald Szeemann's groundbreaking exhibition When Attitudes Become Form at the Kunsthalle Bern.

The 1970s were marked by numerous major exhibitions throughout Europe and the United States. In 1970, a large collection of Beuys's work formed under the artist's own aegis, the Ströher Collection, was installed in the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Darmstadt, which remains the most important public collection of his work. Pontus Hultén invited him to exhibit at Moderna Museet in 1971. Beuys exhibited and performed at each documenta Kassel, most notably with The Honeypump at the FIU Workplace in 1977 and with 7,000 Oaks in 1982. He showed four times at the Edinburgh International Festival and represented Germany at the Venice Biennale in 1976 and 1980. In 1980, Beuys took part in a meeting with Alberto Burri at the Rocca Paolina in Perugia, curated by Italo Tomassoni. During his performance, Beuys explained Opera Unica: six blackboards then purchased by the municipality of Perugia and now housed in the Museo civico di Palazzo della Penna in Perugia. A retrospective of his work was held at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, in 1979. In 1984, Beuys visited Japan and showed various works, including installations and performances, while also holding discussions with students and giving lectures. His first Beuys exhibition took place at the Seibu Museum of Art in Tokyo that same year. The DIA Art Foundation held exhibitions of Beuys' work in 1987, 1992, and 1998, and has planted trees and basalt columns in New York City as part of his 7,000 Oaks, echoing his planting of 7,000 oaks each with a basalt stone, a project begun in 1982 for Documenta 7 in Kassel, Germany. Large collections of his multiples are held by Harvard University, the Walker Art Center Minneapolis, and the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, which also has a collection of Beuys vitrines, The Schellmann and D'Offey collections. Most of the Marx collection of Beuys works including The secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland drawings is at The Hamburger Bahnhof Museum, Berlin. Major art museums in Germany have Beuys works including Fond III at Landesmuseum Darmstadt, while Moechengladbach Museum has the Poor House Doors and much more. Beuys also gave a large collection to the Solidarinosc Movement in Poland. Feuerstätte I und Feuerstätte II (Hearth I and Hearth II) and other works are at the Museum for Contemporary Art Basel, and a dedicated museum was created for 'The Museum des Geldes' collection mainly of FIU blackboards from Documenta 6. As well, perennial Beuys exhibitions continue to take place around the world.[71]

Selected exhibitions

[edit]

- 1964 Drawings & Sculptures 1951–1959, Dokumenta 3, Kassel, Germany

- 1965 Explaining Pictures to a Dead Hare, Galerie Schmela, Duesseldorf, Germany

- 1968 Installation, Dokumenta 4, Kassel, Germany

- 1970 Strategy Gets Arts in Edinburgh International Festival, Scotland, Demarco Gallery at Edinburgh College of Art, with The Pack, Arena, and Aktion Celtic Kinloch Rannoch the Scottish Symphony with Henning Christiansen, Edinburgh, UK

- 1972 Documenta 5, Kassel, Germany

- 1972 Vitex Agnus Castus, Lucio Amelio, Modern Art Agency, Naples, Italy

- 1974 Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland. Museum of Modern Art Oxford, UK[72]

- 1974 Art Into Society, Richt Kraefte, ICA London, UK

- 1974 Three Pots for The Poorhouse, Aktion, with Johannes Stüttgen, The Poorhouse, Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh UK

- 1974 Performance lecture, 'Surrender', Belfast College of Art, Belfast, UK

- 1974 Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland, Ulster Museum, Belfast, with lectures in Belfast and Derry, UK

- 1974 Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland, Municipal Gallery of Modern Art, Dublin, with lectures in Dublin, Cork, and Limerick, Ireland

- 1974 Black & White Oil Conference lecture & performance with Buckminster Fuller, Foresthill Schoolhouse, Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, UK

- 1975 Hearth/Feuerstatte from Fasnacht Basel, 1975, Feldman Gallery, New York, and Museum fuer Gegenwaertige Kuenste, Basel, permanent exhibition, Switzerland

- 1976 Tramstop, Germany Pavilion, Venice Biennale, Italy

- 1976 In Defence of the Innocent, where Beuys stood in for Jimmy Boyle at Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, UK

- 1977 Documenta 6, Kassel, FIU public debates (13 workshops including 1984: What is to be done? & Northern Ireland with 'Brain of Europe,' curated by Caroline Tisdall, Beuys himself & Robert McDowell, 800,000 visitors, 100 Days, and installation exhibit: The Honey Pump, Kassel, Germany

- 1977 Skulptur Projekte Münster, Unschlitt/Tallow (Wärmeskulptur auf Zeit hin angelegt) [Heat Sculpture Designed for Long-term Use], Germany[73]

- 1979 Joseph Beuys Retrospective Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, curator: Caroline Tisdall, New York, U.S.[74]

- 1980 Beuys – Burri, Rocca Paolina, Perugia, Italy

- 1980 What is to be done 1984? FIU, curator: Robert McDowell, Demarco Gallery, Hungerstreik fur Jimmy Boyle and law court case under European Declaration of Human Rights to oppose Jimmy Boyle's Transfer to Saughton Prison, Edinburgh International Festival, Scotland, UK

- 1981 Beuys creates The Poorhouse Doors, now at Stadtische Museum, Munchengladbach, Edinburgh, UK

- 1982 Plight, grand piano in room of rolls of felt sound insulation, d'Offay Gallery, London, UK

- 1982 7,000 Oaks plantings, each with a basalt stone (& leftover stones exhibit as End of Twentieth Century, & Lightening with Stag in its Glare, Tate Modern, Mass MOCA, & Guggenheim Bilbao), Documenta 7, Kassel, Germany

- 1982 Beuys in Scotland 1970–1982, The Richard Demarco Gallery, retrospective, Tate Gallery, London, UK

- 1984 Seibu Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan

- 1985 Palazzo Regale, Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, Italy

- 1985 Plight revisited, Anthony d'Offay Gallery with Richard Demarco, London, UK

- 1986 Marisa del Re Gallery, New York City, January–February 1986

- 1986 Memorial Exhibitions: Feldman Gallery, New York, Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh, Arts Council Gallery, Belfast

- 1986 Memorial Exhibition, Fire Bucket, curator Robert McDowell, Demarco Gallery, Edinburgh

- 1993 Joseph Beuys retrospective, Kunsthaus Zurich, Switzerland

- 1993 The Revolution is Us, Tate Liverpool, UK

- 1994 Joseph Beuys retrospective, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, Madrid. Spain

- 1994 Joseph Beuys retrospective, Moderne Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris, France

- 1999 Secret Block for a Secret Person in Ireland, Royal Academy of Arts, London, UK

- 2005 Joseph Beuys and the Celtic World: Scotland, Ireland, and England 1970–85, Tate Modern, London, UK

- 2006 Museum kunst palast, Düsseldorf; Kunstmuseum Bonn; Museum Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin, Germany

- 2006 The David Winton Bell Gallery, Brown University, Providence, U.S.,[75] U.S.

- 2007 Zwirner & Wirth, New York City, U.S.[76]

- 2007 National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia – Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition (Joseph Beuys & Rudolf Steiner)[77]

- 2008/2009 Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin, Germany – Beuys. We are the Revolution, Video at VernissageTV[78]

- 2008–2010 Museum of Modern Art – Focus on Joseph Beuys on Artbase. New York, U.S.[79]

- 2009 Beuys is Here, De La Warr Pavilion, Bexhill on Sea, East Sussex[80]

- 2010 Joseph Beuys – A Revolução Somos Nós ("Joseph Beuys – We are the revolution"), Sesc Pompéia, São Paulo, Brasil[81]

- 2013 Hamburger Bahnhof Art Museum, Berlin

- 2014 Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

- 2012–2015, End of the Twentieth Century & Richtkraefte, Tate Modern, London

- 2015 Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York, ("Joseph Beuys – Multiples from Schlegollection")[82]

- 2016 (continuing through 2019) Joseph Beuys, Artists' Rooms, Tate Modern, London

- 2016 Joseph Beuys and Richard Demarco, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art and Summerhall Arts Centre, July–October, Edinburgh ("Joseph Beuys & Richard Demarco – Beuys in Scotland")[83]

- 2016 Joseph Beuys in 1,000 items, curated by Robert McDowell (ex Beuys assistant & FIU board member), July -October, Summerhall, Edinburgh

- 2018 Joseph Beuys: Utopia at the Stag Monuments, Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac London, April–June, ("Joseph Beuys: Utopia at the Stag Monuments")[84]

- 2019 Joseph Beuys & Leonardo da Vinci in 1,000 items, curated by R.McDowell, Summerhall, Edinburgh ("Joseph Beuys – in 1,000 items")("Joseph Beuys / Leonardo da Vinci – in 1,000 items") [85]

- 2021 Joseph Beuys, The Maria Leuff Foundation, New York

Art market

[edit]The first works Franz Joseph and Hans van der Grinten bought from Joseph Beuys in 1951 cost about €10 each in 2021 currency. Beginning with small woodcuts, they purchased about 4,000 works, creating the largest Beuys collection in the world.[86] In 1967, the 'Beuys Block', a group of first works, was purchased by the collector Karl Ströher in Darmstadt (now part of the Hessisches Landesmuseum).

Beuys' artworks have fluctuated in price in the years since his death, sometimes even failing to reach bid minimums.[87] A bronze sculpture titled Bett (Corsett, 1949/50) sold for US$900,000 (hammer price) at Sotheby's New York in May 2008, a record.[88] His Schlitten (Sled, 1969) sold for $314,500 at Phillips de Pury & Company, New York, in April 2012.[89] At the same auction, a Filzanzug (Felt Suit, 1970) sold for $96,100.[90] This surpassed the previous auction record for a Filzanzug, 62,000 euros (US$91,381.80) at Kunsthaus Lempertz (Cologne, Germany) in November 2007.[91] Details and prices of Beuys's works sold at auction are listed by Artsy.[92]

The artist produced over 600 original multiples in his lifetime. Large sets of multiples are in the collections of the Pinakothek der Moderne in Munich, Germany, Harvard University Art Museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis, and the Kunstmuseum Bonn, Germany. In 2006, the Broad Art Foundation in Los Angeles acquired 570 multiples by Beuys, including a Filzanzug and a Schlitten,[93] thereby becoming the most complete collection of Beuys works in the United States and among the largest collections of Beuys multiples in the world.[94]

See also

[edit]- Beuys, a 2017 documentary film

- Never Look Away, Beuys is depicted sympathetically during his Kunstakademie Düsseldorf years in this 2018 German film based loosely on the life of artist Gerhard Richter

References and notes

[edit]- ^ Cf. Meisterschüler

- ^ Hopper, Kenneth; Hopper, William (2007). The Puritan gift: triumph, collapse, and the revival of an American dream. I.B.Tauris. p. 334. ISBN 978-1-85043-419-1.

- ^ Hughes, Robert (1991). The Shock of the New (revised ed.). New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 444. ISBN 0-679-72876-7.

- ^ a b c d e f g Adriani, Götz, Winfried Konnertz, and Karin Thomas (1979) Joseph Beuys: Life and Works. Trans. Patricia Lech. Woodbury, N.Y.: Barron's Educational Series.

- ^ a b Schmuckli, Claudia (2005) "Chronology and Selected Exhibition History" in Joseph Beuys: Actions, Vitrines, Environments. Tate. p.188. ISBN 978-1-85437-585-8

- ^ Schirmer, Lothar (ed.) (2006) Mein Dank an Lehmbruck. Eine Rede. Schirmer/Mosel, München, p. 44. ISBN 978-3-8296-0225-9

- ^ Ermen, Reinhard (2007) Joseph Beuys. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. p. 11

- ^ "Joseph Beuys". Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ The implications are ambiguous. Germany had been at war since September 1939, military service was mandatory, and volunteering was one way to influence deployment.

- ^ Adams, David (2014). "Joseph Beuys: Pioneer of a Radical Ecology". Art Journal. 51 (2): 26–34. doi:10.1080/00043249.1992.10791563. ISSN 0004-3249.

- ^ Pasik, Yakov (19 April 2006). Еврейские поселения в Крыму (1922–1926). ucoz.com

- ^ Tisdall, pp. 16–17.

- ^ Ermen, Reinhard (2007) Joseph Beuys. Rowohlt-Taschenbuch-Verlag. p. 153.

- ^ For a detailed account see Nisbet, "Crash Course – Remarks on a Beuys Story" in Mapping the Legacy.

- ^ For a recent analysis of the reception of this story, see Krajewski, Beuys. Duchamp

- ^ Stiftung Museum Schloss Moyland, Sammlung van der Grinten, Joseph Beuys Archiv des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen (eds.) (2001) Joseph Beuys, Ewald Mataré and Eight Cologne Artists. B.o.s.s Druck und Medien, Bedburg-Hau. p.25.

- ^ Invar Hollaus, "Heerich, Erwin". In Allgemeines Künstler-Lexikon, vol. 71 (2011), p.44.

- ^ Günter Grass, (2006) Peeling the Onion (autobiography).

- ^ "Elias Maria Reti – Künstler – Biografie". www.eliasmariareti.de (in German). Archived from the original on 18 December 2018. Retrieved 18 December 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Durini, Lucrezia De Domizio. The Felt Hat: Joseph Beuys A Life Told. Milano, Charta, 1997

- ^ "Democracy is Funny [Demokratie ist lustig]". The multiples of Joseph Beuys. Munich: Pinakothek der Moderne. 1973.

- ^ a b Ulmer, G. (2007). Performance: Joseph Beuys in Joseph Beuys The Reader. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press. pp. 233–236. ISBN 978-0-262-63351-2

- ^ Sharp, W. (1969). Interview as quoted in Energy Plan for the Western man – Joseph Beuys in America, compiled by Carin Kuoni. Four Walls Eight Windows, New York, 1993, p.85. ISBN 1-56858-007-X

- ^ Sotheby's catalog, 1992

- ^ a b c d "Henry Moore Institute". Archived from the original on 22 March 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Beuys, J. (1975). Jeder mensch ein kunstler. tate.org.uk

- ^ "Walker Art Center – Contemporary Art Museum – Minneapolis". www.walkerart.org.

- ^ Ulmer, Gregory (1985). Applied Grammatology: Post(e)-Pedagogy from Jacques Derrida to Joseph Beuys. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 230. ISBN 978-0-8018-3257-4.

- ^ Tisdall, Caroline (2010). Joseph Beuys. Thames & Hudson. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-500-54368-9.

- ^ Halpern, John (Director) (15 April 1988). [Joseph Beuys / TRANSFORMER] (Television sculpture). New York City: I.T.A.P. Pictures.

- ^ Rosental, Norman; Bastian, Heiner (1999). Joseph Beuys: The Secret Block for a Secret Person In Ireland. Art Books Intl Ltd.

- ^ Ulmer, Gregory (1985). Applied Grammatology: Post(e)-Pedagogy from Jacques Derrida to Joseph Beuys. Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 238–240. ISBN 978-0-8018-3257-4.

- ^ Russell, John (25 January 1986). "JOSEPH BEUYS, SCULPTOR, IS DEAD AT 64". nytimes.com. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Chahil, Andre (13 October 2015) Wien 1985: Phänomen Fax-Art. Beuys, Warhol und Higashiyama setzen dem Kalten Krieg ein Zeichen. Chahil Art Consulting (German)

- ^ a b Westcott, James (9 November 2005). "Marina Abramovic". ARTINFO. Archived from the original on 4 December 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2008.

- ^ a b c Tisdall, p.94

- ^ Tisdall, p.97

- ^ a b c Tisdall, p.95

- ^ a b Verwoert, Jan (December 2008). "The Boss: On the Unresolved Question of Authority in Joseph Beuys' Oeuvre and Public Image". e-flux.com. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Meador, Lana Shafer (8 November 2015). "Joseph Beuys and Martin Kippenberger: Divergent Approaches to Relational Aesthetics". frenchandmichigan.com. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ a b c d e Tisdall, p.168

- ^ a b Tisdall, p.171

- ^ Naidoo, Alexia (18 January 2016). "Beuys: Unwrapping the Enigma". National Gallery of Canada. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Workman, Michael (30 March 2016). "Charlotte Moorman: Chicago exhibit reveres avant garde's renegade cellist". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ Dow, Steve (10 September 2018). "In a house without love, piano was the key for sculptor Ken Unsworth". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ McLaughlin, Dan (30 April 2020). "Joseph Beuys, or Dissolution into Brand (Copy)". danmclaughlinartist.com. Retrieved 18 August 2020.

- ^ a b Schneede, Uwe M. (1998) Joseph Beuys: Die Aktionen. Gerd Hatje. p. 330. ISBN 3-7757-0450-7

- ^ "American Beuys". Johan Hedback. Archived from the original on 16 March 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Eisinger, Dale (9 April 2013). "The 25 Best Performance Art Pieces of All Time". Complex. Retrieved 28 February 2021.

- ^ "Strategy: Get Arts". Archived from the original on 27 July 2011. Retrieved 10 December 2009.

- ^ Oman, Hiltrud (1998). Die Kunst auf dem Weg zum Leben: Joseph Beuys. Heyne TB.

- ^ Beuys's statement dated 1973, first published in English in Caroline Tisdall (1974) Art into Society, Society into Art. ICA, London, p. 48. Capitals in original.

- ^ Reames, Richard (2005) Arborsculpture: Solutions for a Small Planet, p. 42, ISBN 0-9647280-8-7.

- ^ "Dia Art Foundation – Sites". Diaart.org. Archived from the original on 18 May 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ Video on YouTube

- ^ "Pop statt Böller – Joseph Beuys: Sonne statt Reagan – Musik – fluter.de". Archived from the original on 11 February 2013. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Beuys. "Sun Instead of Reagan". YouTube. Retrieved 21 April 2011.

- ^ Published in Reinische Post on 3 October 1972, written by Broodthaers on 25 September 1972.

- ^ Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. (1980). "Beuys: The Twilight of the Idol". Artforum. 5 (18): 35–43.

- ^ Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. (1980). "Beuys: The Twilight of the Idol". Artforum. 5 (18): 51.

- ^ While correctly pointing out the fictionalisation, Buchloh mistakenly identifies the plane crash as having entered Beuys' biography as early as his 1964 Lebenslauf/Werklauf.

- ^ Germer, Stefan (1988). "Haacke, Broodthaers, Beuys". October. 45. JSTOR: 63–75. doi:10.2307/779044. JSTOR 779044.

- ^ Krauss, Rosalind E. (1997) "No to ... Joseph Beuys" in Krauss, R.E. and Bois, Yve-Alain Formless: A User's Guide. Zone. pp. 143–146. ISBN 978-0-942299-43-4

- ^ Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. "Reconsidering Joseph Beuys, Once Again", pp. 75–90 in Mapping the Legacy

- ^ Ray, Gene "Joseph Beuys and the After-Auschwitz Sublime", pp. 55–74 in Mapping the Legacy

- ^ Mesch, Claudia and Michely, Viola, eds. Joseph Beuys: the Reader. MIT Press, 2007.

- ^ Mesch, Claudia (2013) "Sculpture in Fog: Beuys' Vitrines," in John Welchman, ed., Sculpture and Vitrine. Ashgate and The Henry Moore Institute. pp. 121–142. ISBN 978-1-4094-3527-3

- ^ Mesch, Claudia: Joseph Beuys. London: Reaktion Books, 2017. Chinese edition, Beijing: Icons, 2024. Italian edition, Milan: postmedia books, 2024.

- ^ Lerm Hayes (2004) Joyce in Art, Visual Art Inspired by James Joyce. Lilliput Press

- ^ Fer (2004) The Infinite Line: Remaking Art After Modernism. Yale

- ^ Potts, Alex (2004). "Tactility: The Interrogation of Medium in Art of the 1960s". Art History. 27 (2). Wiley: 282–304. doi:10.1111/j.0141-6790.2004.02702004.x.

- ^ "Joseph Beuys – Artist Biography". Archived from the original on 22 November 2010.

- ^ Walker, John A. (June 1974). "Joseph Beuys at Museum of Modern Art, Oxford (1974)". Studio International. 187 (967): 10–11. Archived from the original on 23 May 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ Skulptur Projekte Archiv: Joseph Beuys, Unschlitt/Tallow.

- ^ Boch, Richard (2017). The Mudd Club. Port Townsend, WA: Feral House. pp. 214–215. ISBN 978-1-62731-051-2. OCLC 972429558.

- ^ Another View of Joseph Beuys. David Winton Bell Gallery. Brown University

- ^ "David Zwirner". www.davidzwirner.com.

- ^ "Joseph Beuys & Rudolf Steiner Imagination, Inspiration, Intuition". Archived from the original on 16 October 2007. Retrieved 23 November 2007.

- ^ "Beuys. We are the Revolution / Hamburger Bahnhof – Museum für Gegenwart, Germany Berlin". Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Focus on Joseph Beuys". Artabase. Archived from the original on 7 August 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Beuys Is Here". Bexhill, East Sussex: The De La Warr Pavilion. 27 September 2009.

- ^ "SÃO PAULO POLO DE ARTE CONTEMPORÂNEA". Archived from the original on 19 May 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2010.

- ^ "Multiples from the Reinhard Schlegel Collection – Joseph Beuys – Exhibitions". Mitchell-Innes & Nash.

- ^ "Odd couple: How Joseph Beuys and Richard Demarco helped change British art". BBC. 15 August 2016.

- ^ "Joseph Beuys: Utopia at the Stag Monuments". galleriesnow.net. 4 August 2018.

- ^ "JOSEPH BEUYS / LEONARDO DA VINCI". 4 August 2019.

- ^ Chang, Helen (Janueary 11, 2008)Why I Buy: Art Collectors Reveal What Drives Them. The Wall Street Journal

- ^ Art Sales. "Art market news: Joseph Beuys suit sells for $96,000". Telegraph. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- ^ "Sotheby's – Catalogue". Sothebys.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "JOSEPH BEUYS – Sled, 1969". Phillips. Archived from the original on 31 January 2013.

- ^ Gleadell, Colin (1 May 2012). "Art market news: Joseph Beuys suit sells for $96,000". Telegraph.co.uk. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Phibro's Andrew Hall Exhibits Beuys; Blind Men Use Power Tools". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "Joseph Beuys – Auction Results and Sales Data". Artsy. List of works sold and prices (registration needed to see prices), updated as required.

- ^ "Eli Broad's Foundation Buys 570 Works by German Artist Beuys". Bloomberg News. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ^ "» LACMA: Broad, Beuys, & BP". Art-for-a-change.com. 28 March 2007. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

Cited sources

[edit]- Ray, Gene, ed. (2001). Joseph Beuys: Mapping The Legacy. Distributed Art Publishers. ISBN 978-1-891024-03-0.

- Tisdall, Caroline (1979). Joseph Beuys. New York: Guggenheim Museum.

Further reading

[edit]- Adams, David: "Joseph Beuys: Pioneer of a Radical Ecology," Art Journal, vol. 51, no. 2 Summer 1992. 26–34; also published in The Social Artist vol. 2, no. 1 Spring 2014: 3–13.

- Adams, David: "From Queen Bee to Social Sculpture: The Artistic Alchemy of Joseph Beuys," Afterword in Rudolf Steiner, Bees. Hudson, N.Y.: Anthroposophic Press, 1998, pp. 187–213. ISBN 0-88010-457-0.

- Bastian, Heiner: Joseph Beuys: The secret block for a secret person in Ireland. Text by Dieter Koepplin. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel, 1988.

- Beuys, Joseph: What is Money? A discussion. Trans. Isabelle Boccon-Gibod. Forest Row, England: Clairview Books, 2010.

- Borer, Alain. The Essential Joseph Beuys. London: Thames and Hudson, 1996.

- Buchloh, Benjamin H.D., Krauss, Rosalind, Michelson, Annette: 'Joseph Beuys at the Guggenheim,' in: October, 12 (Spring 1980), pp 3–21.

- Chametzky, Peter. Objects as History in Twentieth-Century German Art: Beckmann to Beuys. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2010.

- De Duve, Thierry: Kant After Duchamp, Cambridge (Mass.): MIT Press, 1996. ISBN 9780262041515.

- Hintzen, Sigrun: Joseph Beuys und die Musik, Tectum Verlag, Baden-Baden, 2021, ISBN 978-3-8288-4666-1

- Krajewski, Michael: "Beuys. Duchamp: Two Stories. Two Artist Legends." In: Beuys & Duchamp. Artists of the Future. Magdalena Holzhey, Katharina Neuburger, Kornelia Röder, eds., Krefelder Kunstmuseen, Berlin 2021, p. 337-345, ISBN 978-3-7757-5068-4

- Masters, Greg, "Joseph Beuys: Past the Affable"; from For the Artists, Critical Writing, Volume 1 .Crony Books, 2014.

- Mesch, Claudia: Joseph Beuys. London: Reaktion Books, 2017. Chinese edition, Beijing: Icons, 2024. Italian edition, Milan: postmedia books, 2024.

- Mesch, Claudia and Michely, Viola, eds. Joseph Beuys: the Reader. MIT Press, 2007.

- Mühlemann, Kaspar: Christoph Schlingensief und seine Auseinandersetzung mit Joseph Beuys. Mit einem Nachwort von Anna-Catharina Gebbers und einem Interview mit Carl Hegemann (Europäische Hochschulschriften, Reihe 28: Kunstgeschichte, Bd. 439), Peter Lang Verlag, Frankfurt am Main u.a. 2011. ISBN 978-3-631-61800-4.

- Murken, Axel Hinrich: Joseph Beuys und die Medizin. F. Coppenrath, 1979. ISBN 3-920192-81-8.

- Oman Hiltrud: Joseph Beuys. Die Kunst auf dem Weg zum Leben. München, Heyne, 1998. ISBN 3-453-14135-0.

- Potts, Alex: 'Tactility: The Interrogation of Medium in the Art of the 1960s,' Art History, Vol.27, No.2 April 2004. 282–304.

- Stachelhaus, Heiner. Joseph Beuys. New York: Abbeville Press, 1991.

- Temkin, Ann, and Bernice Rose. Thinking is Form: The Drawings of Joseph Beuys (exh. cat., Philadelphia Museum of Art). New York: Thames and Hudson, 1993.

- Tisdall, Caroline: Joseph Beuys: We Go This Way, London, 1998. ISBN 978-1-900828-12-3.

- Valentin, Eric, Joseph Beuys. Art, politique et mystique, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2014. ISBN 978-2-343-03732-5.

- Beuys Brock Vostell. Aktion Demonstration Partizipation 1949–1983. ZKM – Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie, Hatje Cantz, Karlsruhe, 2014. ISBN 978-3-7757-3864-4.

- Rupprecht, Caroline. "Shamanic Performances: Joseph Beuys's Der Eurasier, Eurasia Siberian Symphony, and Auschwitz Demonstration." Asian Fusion: New Encounters in the Asian-German Avant-Garde. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2020. 149–181.

External links

[edit]- Archivio Conz

- Joseph Beuys at the Museum of Modern Art

- Joseph Beuys Site includes articles, chronology, bibliography and gallery of exhibition posters.

- The Beuys Homepage by "Free International University"(FIU)

- Details of the 7,000 oaks project West 22nd Street, 10th to 11th Ave, New York City

- Joseph Beuys Music at Ubuweb

- Audio of Joseph Beuys "Ja Ja Ja Ne Ne Ne", 1970, Mazzotta Editions, Milan at Ubuweb

- Walker Art Information Center

- Articles about Beuys

- Beuys' 1978 newspaper article "Appeal for an Alternative"

- Picture gallery

- The Social Sculpture Research Unit